1990s

1990s

1999

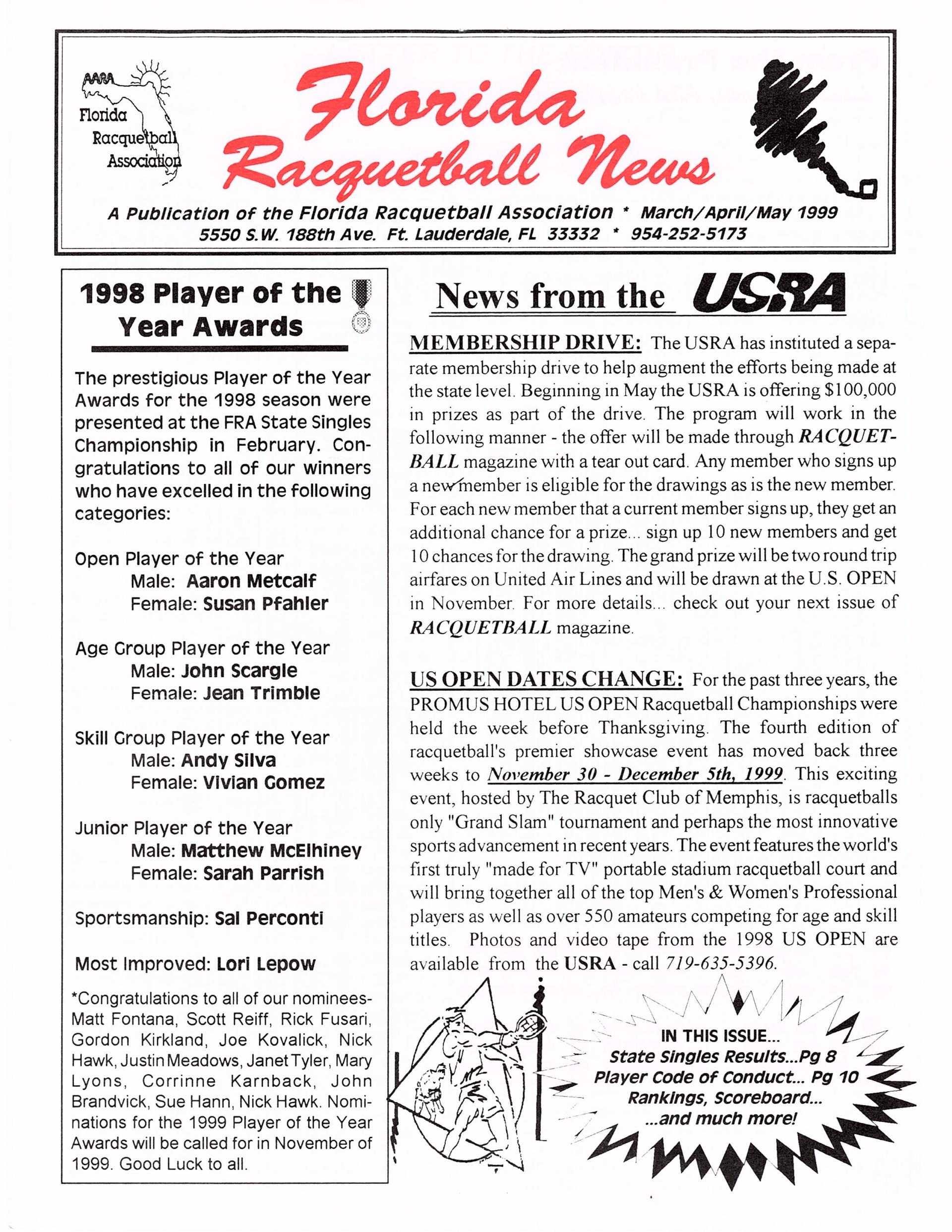

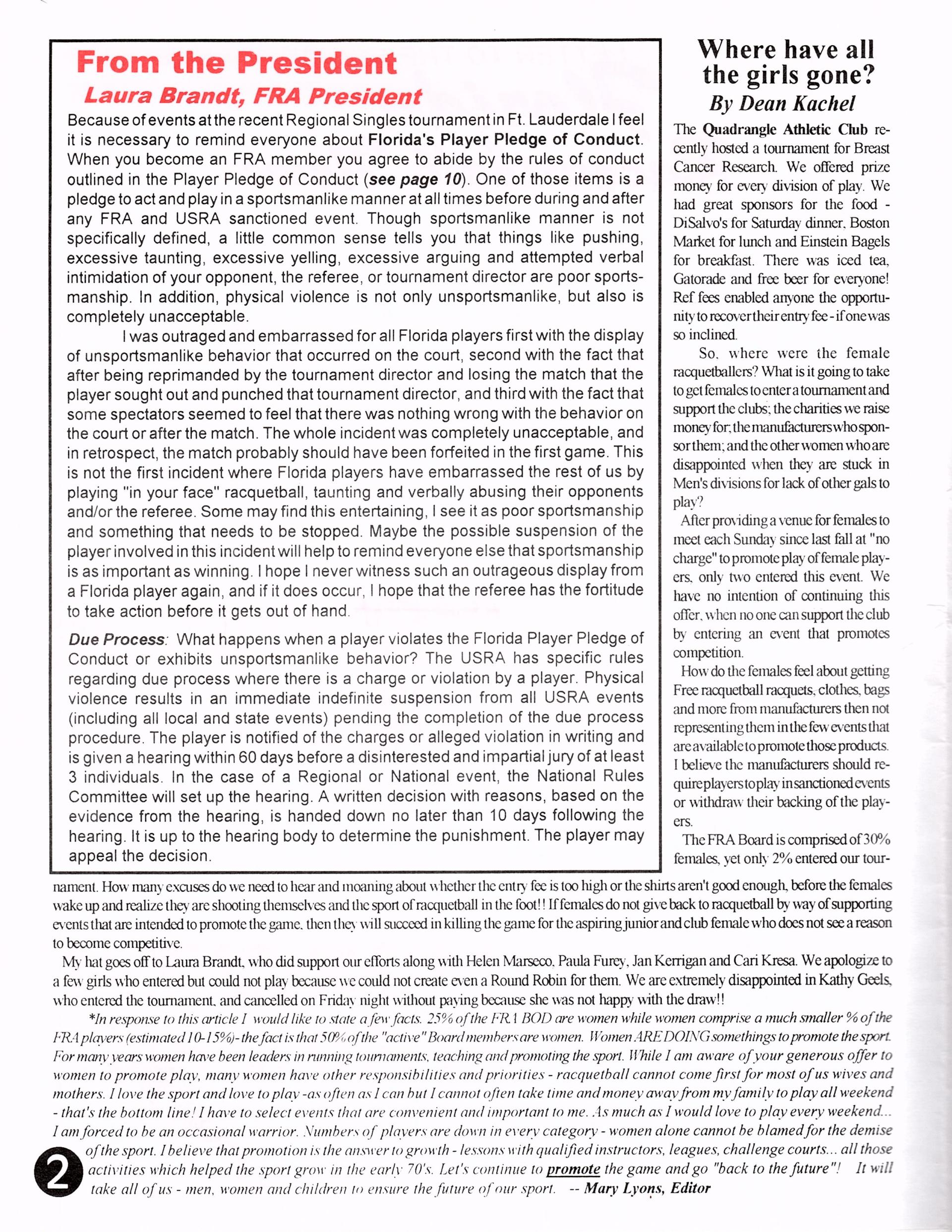

March

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

May

MAN WIELDING A DANGEROUS WEAPON FEARLESS SUDSY MONCHIK HAS SLICED AND DICED HIS WAY TO THE TOP OF HIS SPORT -

LINK TO ORIGINAL

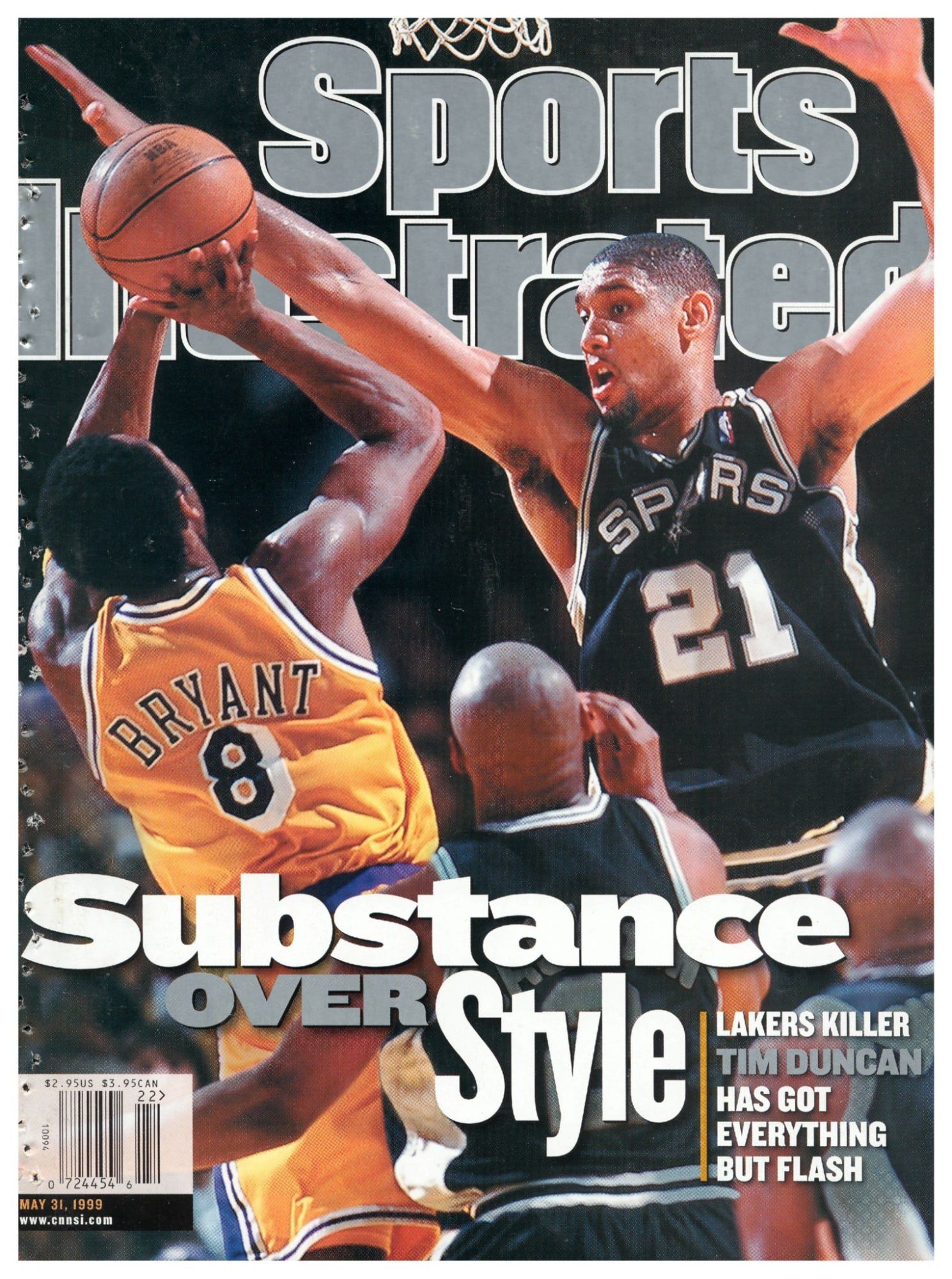

May 31, 1999

BY FRANZ LINDZ

Sudsy Monchik loves freedom, hates tyranny. We know this because his favorite film is Braveheart, the Oscar-winning kilt-fest about 13th-century Scottish freedom fighter Sir William Wallace.

"If I'd lived in Wallace's time, I would have been pillaging right at his side," says the 20th-century Staten Island racquetball player. "William Wallace was the Man!"

Monchik preps for matches by watching Braveheart (he travels with the video), has memorized long stretches of Braveheart dialogue, has even installed a Braveheart screen saver on his laptop. Boot up the computer, and out spews Wallace's rousing pep talk before the Battle of Stirling Bridge. Shut it down and you hear, "Every man dies; not every man really lives."

As Sudsy sees it, the reel-life Wallace is not so different from the real-life Monchik. Both are brash charmers who display an insouciant impudence. "In the movie Wallace combined cockiness with confidence," Monchik says. "What he believed in, he fought for." Monchik believes mostly in himself, and he fights to maintain his place atop the pro racquetball tour. His diving, vaulting, crowd-rousing rallies are Wallacian in their fury: He has gouged, hacked and hewed his way to the No. 1 ranking in three of the last four seasons. "My racket is my sword, my slicer and dicer," he says. He tilts his head back and closes his eyes, his posture for expounding at length. "I'm pals with each opponent I face, but once the door closes, I want to rip out his eyes and step on his trachea."

Monchik, 24, is 5'9", with a pale, rubbery face and large staring eyes of a blazing fluorescent green. "Sudsy schmoozes with everyone and never gets in a bad mood," says fellow pro Jason Mannino, a friend since childhood. "Even at his most obnoxious, he's totally lovable."

A totally lovable homeboy. Until this month he still lived with his parents. "I just moved in with my fiancee, Lisa," he says. "She's really understanding--even let me hang a Braveheart poster on the refrigerator." They are getting married on July 10, in Bermuda. Does she know what she's in for? "Come on, she's got the Messiah!," he says, incredulous. "She's seen me play! I own 'em once they see me play. I'm where the action is."

He has been an action guy since he was a little Mon chick. "Even as a baby they tell me I didn't crawl: I sprinted," he says. "There was no walking involved."

Monchik's moniker was hung on him in utero. His father, a New York City cop, came up with Sudsy while the boy was still submerged in amniotic fluid. "I used to say my nickname came from licking the foam off the tops of beers as a toddler," says Sudsy, whose given name is Walter. "The truth is I don't drink beer--can't stand the taste. But if Budweiser or Coors wants to sponsor me, I'll drink all they want me to."

As it turns out, Monchik isn't his birth name, either. When Sudsy was five his parents divorced, and he went to live with his mother and her new husband, Allen Monchik. Sudsy's stepfather had a stake in several local health clubs: At age seven the tyke wandered into the racquetball courts and started banging a ball around. Seeing the boy's interest, the elder Monchik hired pro Ruben Gonzalez to give the younger Monchik lessons.

Racquetball came easy to Sudsy. "Too easy," says Gonzalez, who was ranked No. 1 on the pro circuit in 1988. At practice Gonzalez began asking the boy if he was tired. If Sudsy said yes, he would have to pay Gonzalez a dollar. "I realized the only way to keep my allowance was to keep saying no," says Sudsy, "even if I was throwing up my guts. Ruben hoped that by training me that way, stamina and consistency would develop."

They did develop, quickly. Sudsy became the greatest junior player in the sport's history, winning national titles in every age division from eight to 18. He also became the sport's greatest junior prankster. If a hotel fountain started foaming over or a bottle rocket blasted out a hotel window, Sudsy would be the prime suspect. "I would always get blamed for everything," he says. "Everyone knew I knew who was responsible, but I would never rat."

At 19, in only his fifth pro event, Monchik unsettled his more seasoned peers by winning the 1994 nationals. Gonzalez was already unsettled--in an earlier tournament Monchik had beaten him 2-11, 11-5, 11-8, 11-8 in their first pro match. (To this day Gonzalez hasn't beaten his protege in the pros.) At the end of the '94-95 season, Monchik joined the racquetball elite with consecutive victories over Cliff Swain, whom Racquetball Magazine had anointed the "best of the best."

For the last five years Swain and Monchik have been the foremost players in the world, averaging $45,000 to $60,000 in winnings on the tour. The mild, crafty Swain is a kind of court conjurer: In moments of crisis he seems to pluck brilliant shots out of his sleeves like silk scarves. Monchik is more of a swashbuckler, slashing and adventurous. "Sudsy has great foot speed--he gets every ball that fails to roll out," says tour commissioner Hank Marcus. "But his hand speed makes him really excel. No one ever hit the ball consistently harder."

Monchik's backhand is as fast as his forehand, which has been clocked at more than 180 mph. The ball flies off his racket explosively. "He's like a thug out there, an incredibly skilled thug," says tour player Eric Muller. "As bullying as he can be physically, mentally he's still only scratching the surface. If Sudsy ever fully focused, he could do some scary things on the court."

Swain's reign as No. 1 ended when Monchik wrung the crown from him in the final tournament of the '95-96 campaign. Monchik won the title outright the next season, and Swain recaptured it in '97-98. Swain's comeback was due partly to subtle adjustments in his game--adding a lob serve, hanging back on the floor—and partly to injuries suffered by Monchik: a separated shoulder, a broken big toe and a badly sprained left ankle. "Sure, I was hurt," says Monchik. "But being hurt is no excuse."

This season Swain and Monchik have met in the singles finals of nine tournaments. Monchik has won eight of the matches, including the last seven in a row. In two of them, he blanked Swain in a game, denying him a single point. "Cliff is still pounding everyone else," says Monchik. "Everyone else but me. He just turned 33. Don't think I don't count the years."

Their last encounter--on April 25 at the nationals in Las Vegas--was perhaps the most humbling for Swain. Monchik aced him 17 times in an 11-6, 11-3, 11-2 wipeout that brought his tour winnings to about $60,000 for the year. Now, with only one event left in the season, the No. 1 ranking is safely in Monchik's pocket. "Actually, the passing of the torch happened a few years ago," says Mannino. "Last year Cliff got in his last licks, but the rivalry is over. Sudsy plays on a different planet than the rest of us."

Yet Swain still bravely insists that he and Monchik are equal. He pins his recent results on poor concentration.

"If that's what Cliff thinks, fine," Monchik says. "What else can he say? He's constantly getting pounded by a guy who hits the ball at Mach 5. I feel his pain. But you know why the Yankees creamed the Padres in last year's World Series? They were better."

Asked if he thinks the tour has marketed the more outgoing Monchik at his expense, Swain gives a quick look of focused contempt. "It makes me a little angry," he grumbles. "In the eyes of those promoting the sport, if you're not cocky or flaky, you're not worthy of promotion. When I win a tournament, it's SWAIN WINS AGAIN. When Sudsy wins, it's HE'S UNSTOPPABLE!"

Monchik mulls this thought over breakfast in a Las Vegas coffee shop. "I'm sure if I ever reach Cliff's age, I'll have some 24-year-old punk to worry about," he says, head tilted back, eyes closed. "Cliff may be the greatest racquetball player ever, but how long before Sudsy surpasses him?"

Without pausing, Sudsy provides the answer: "Not long at all."

"I'm pals with each opponent I face, but once the door closes I want to step on his trachea."

COLOR PHOTO: SIMON BRUTY

COLOR PHOTO: MIKE BOATMAN/U.S.OPEN RACQUETBALL CHAMPIONSHIPS SWASHBUCKLER SUDSY Monchik's backhand and forehand have topped 180 mph.

1998

Back to Top

1997

March

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

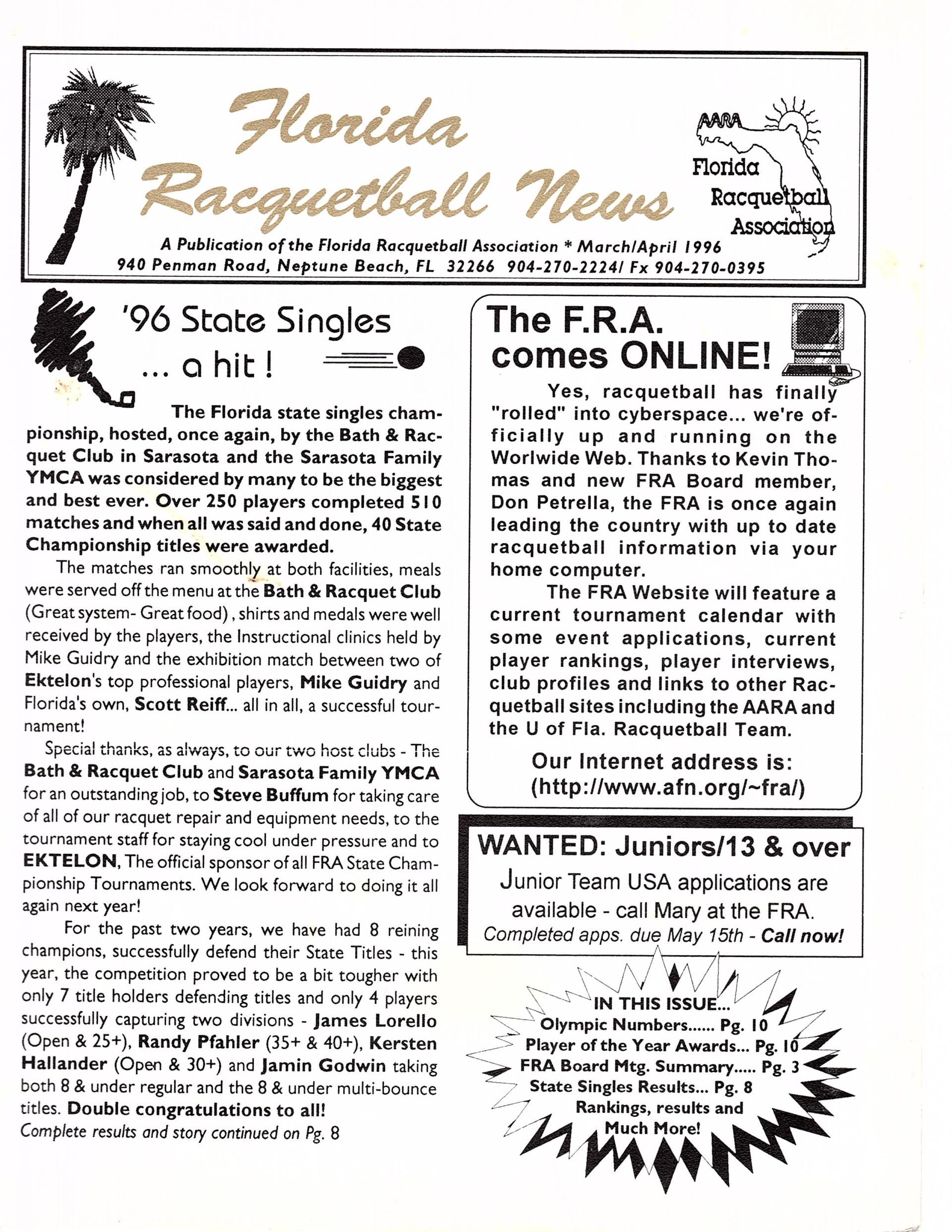

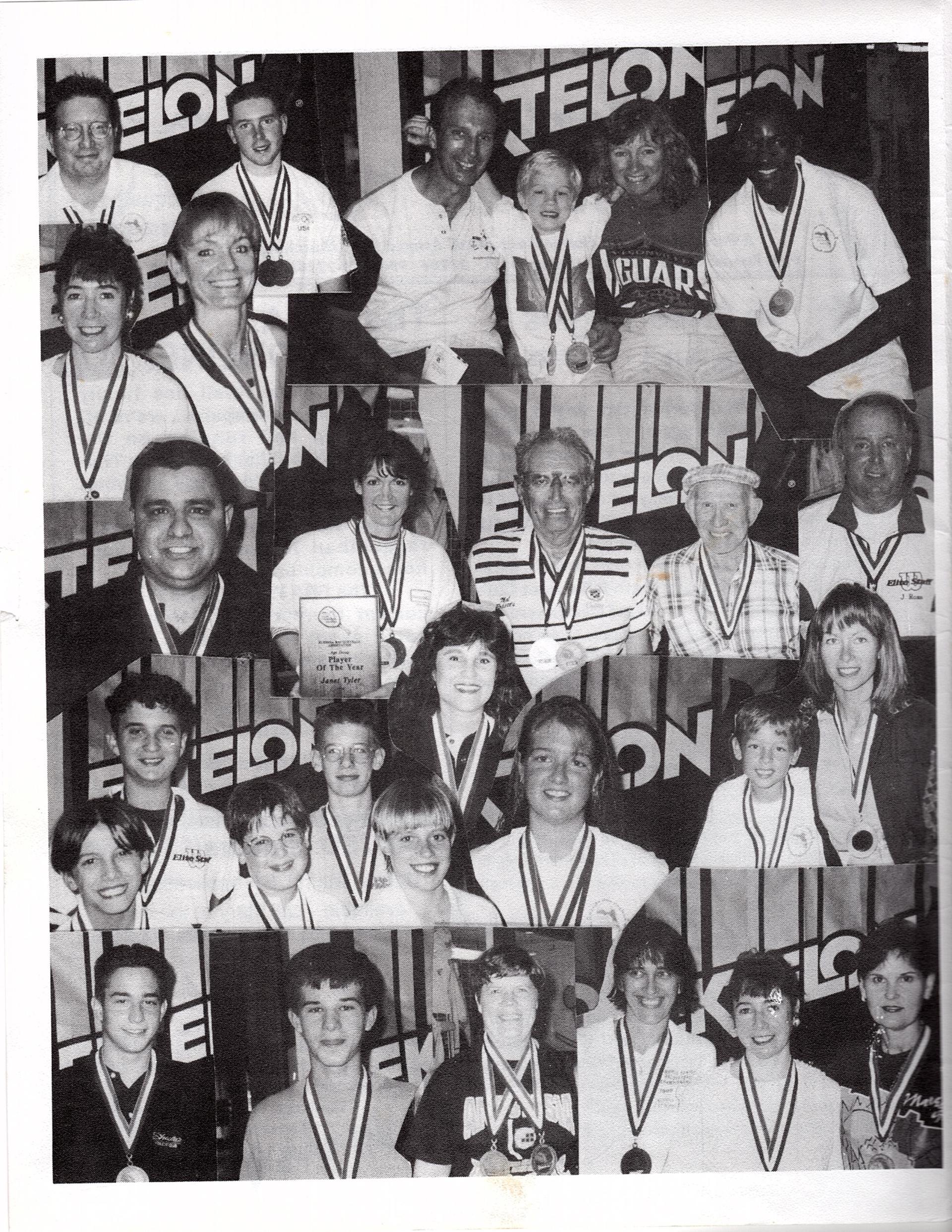

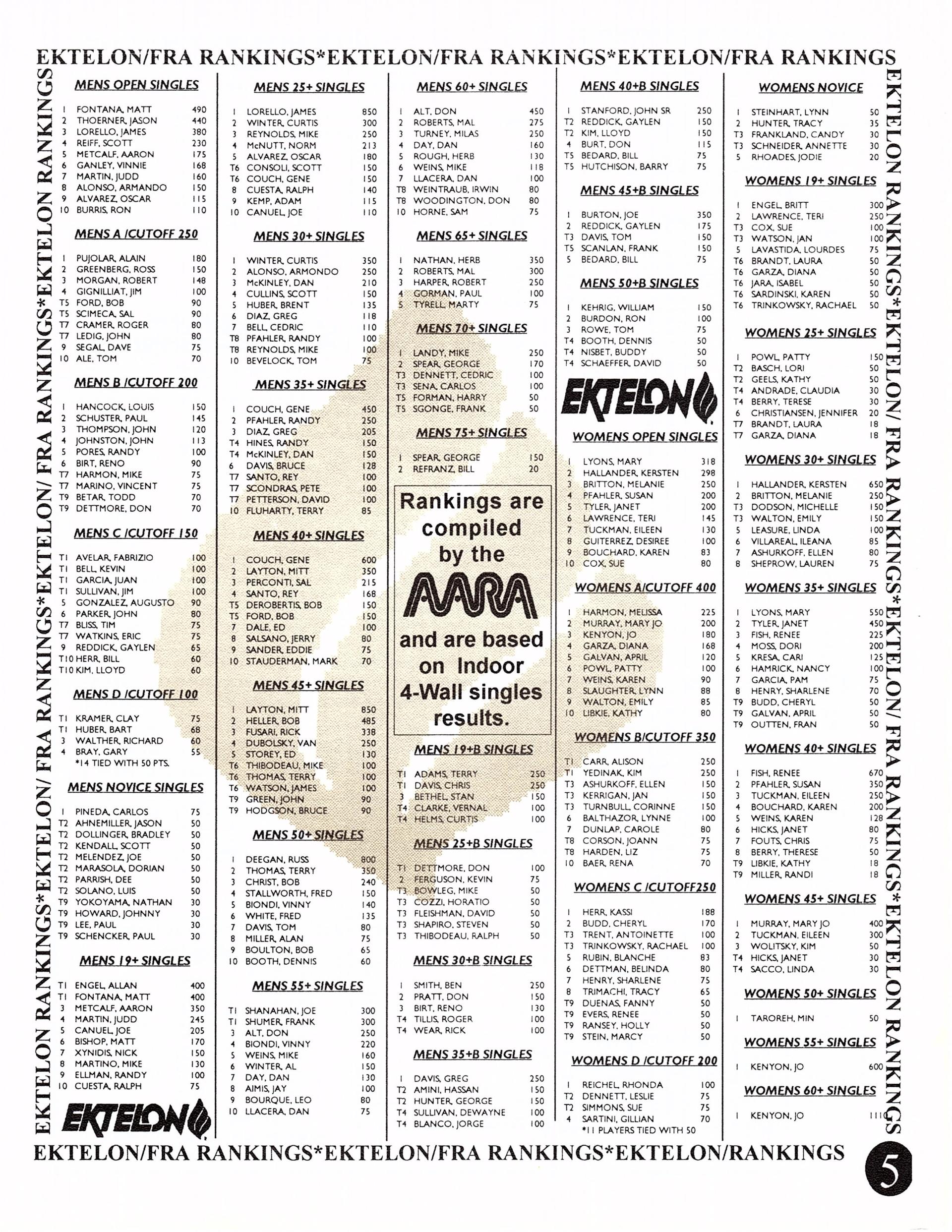

1996

March

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

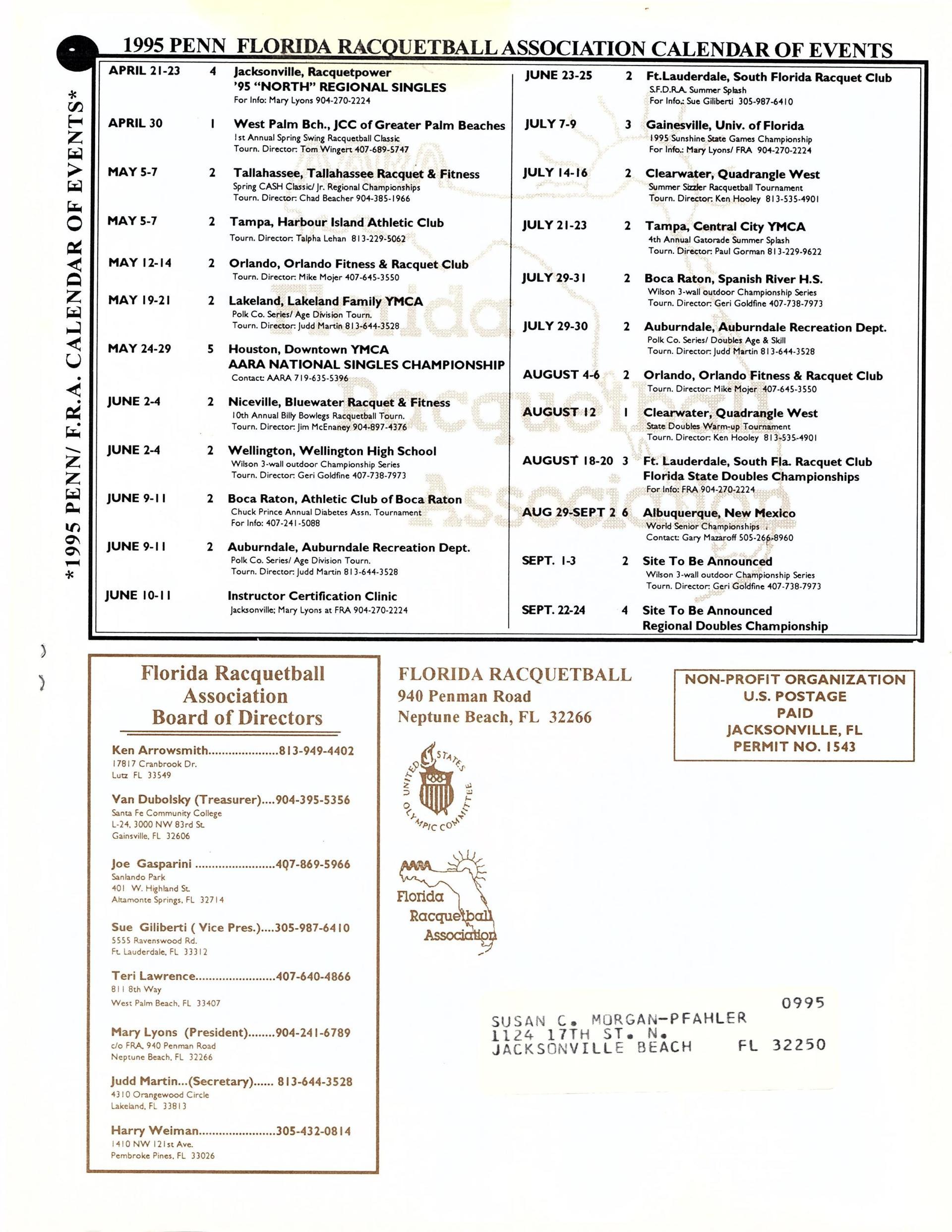

1995

March

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

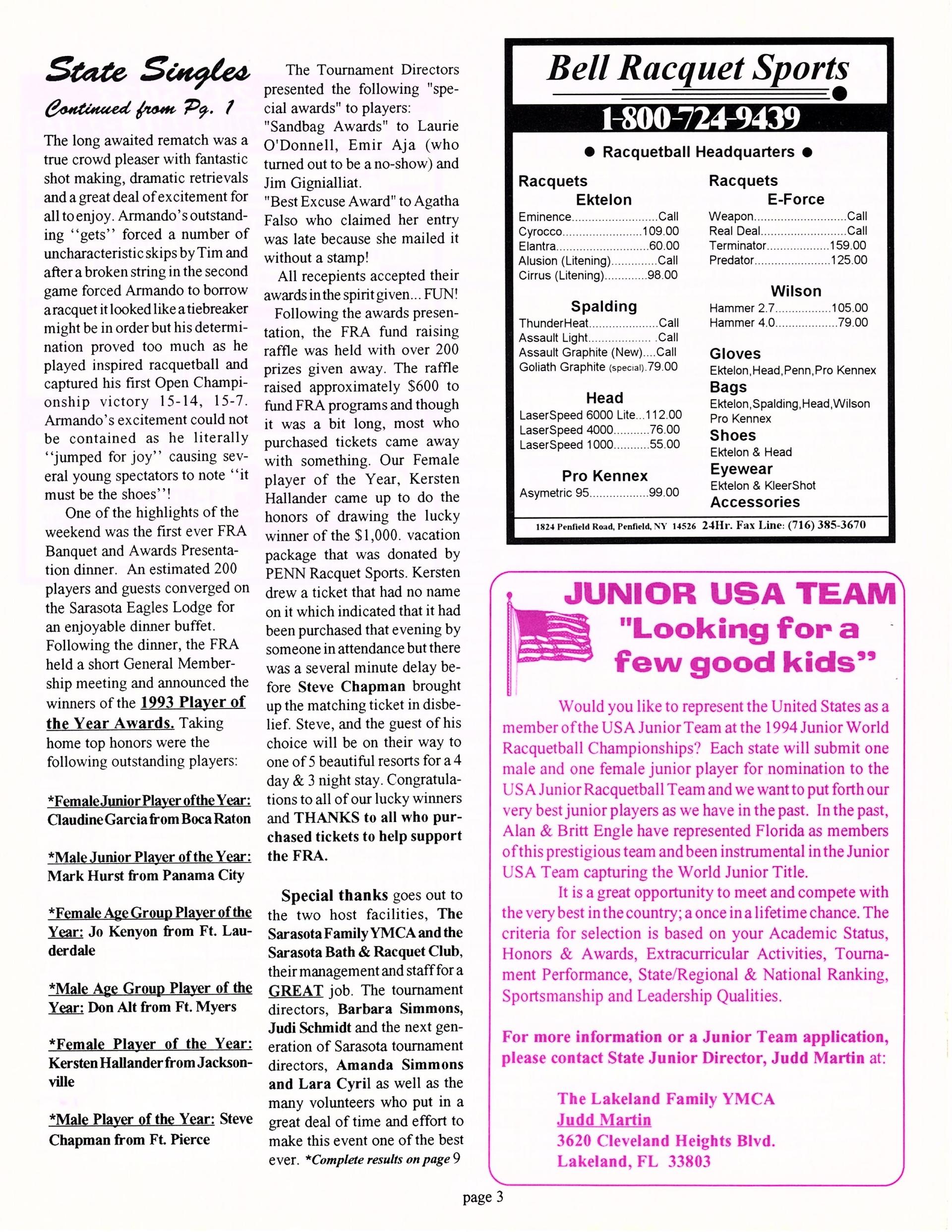

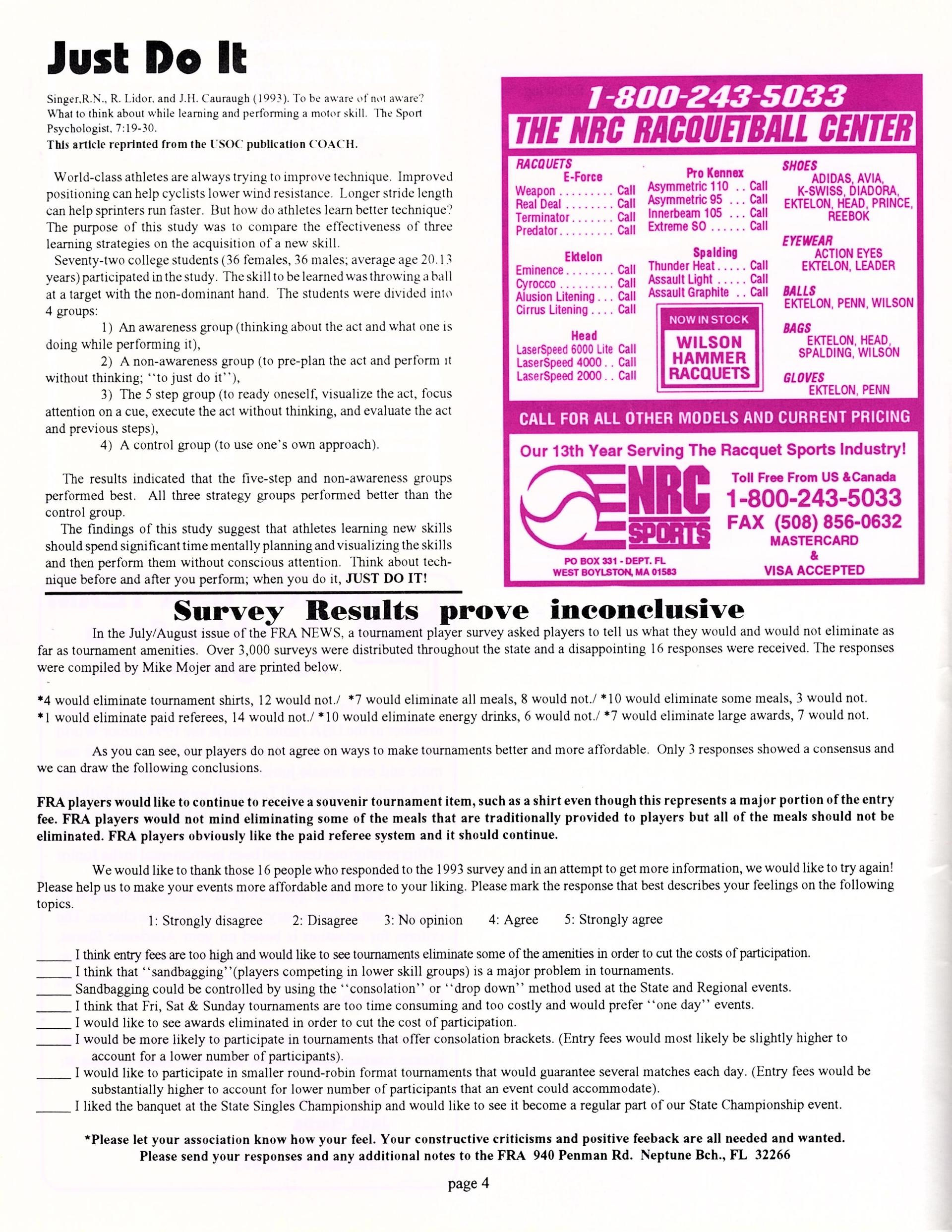

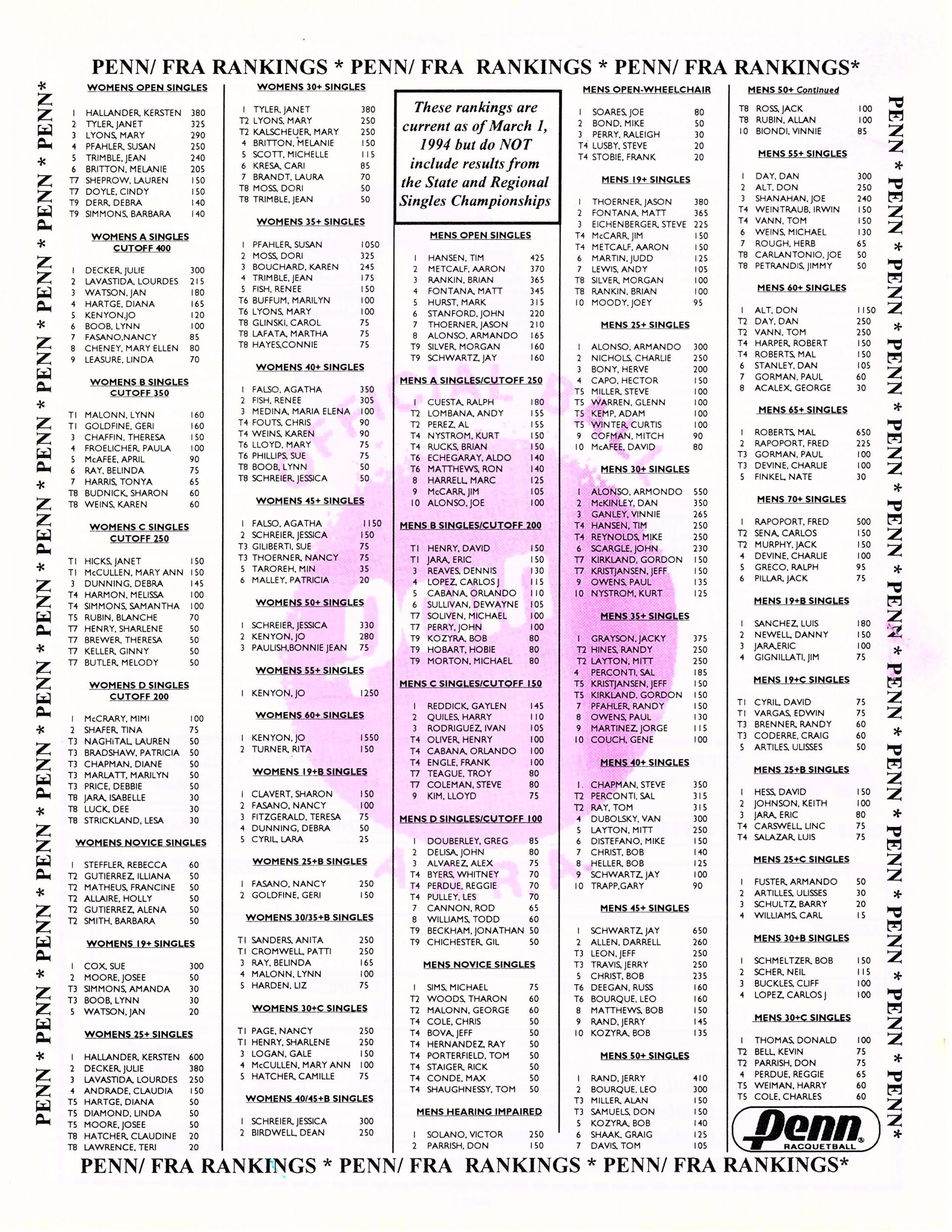

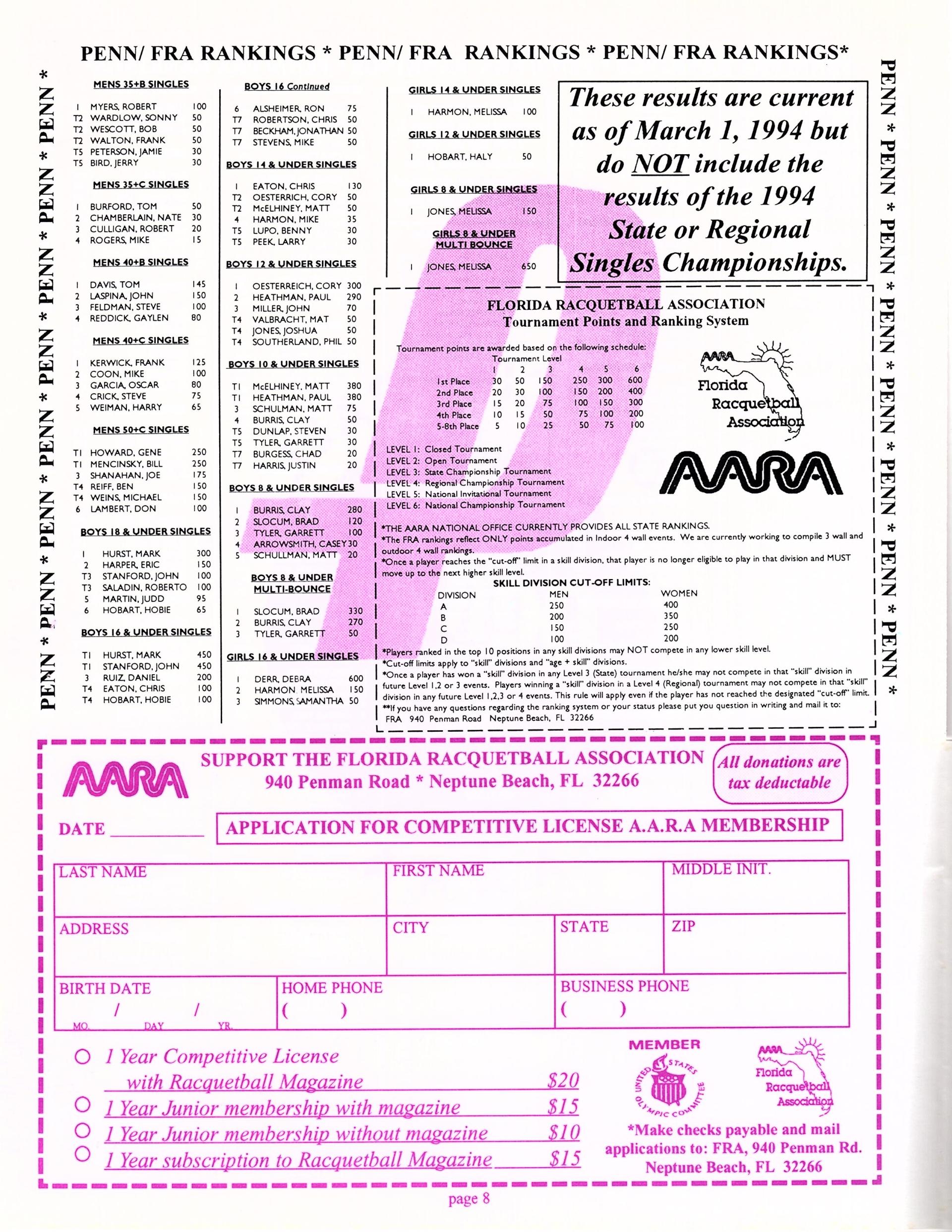

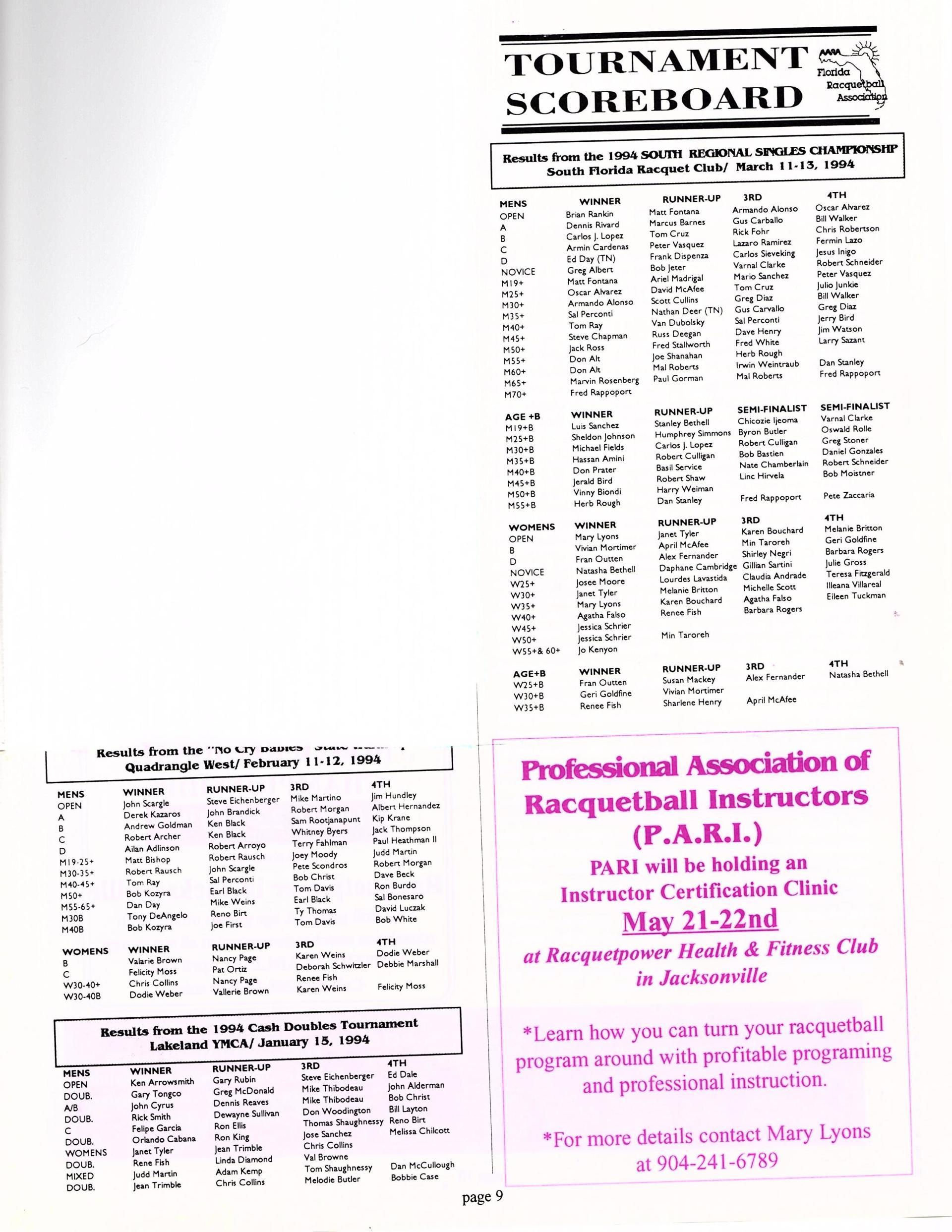

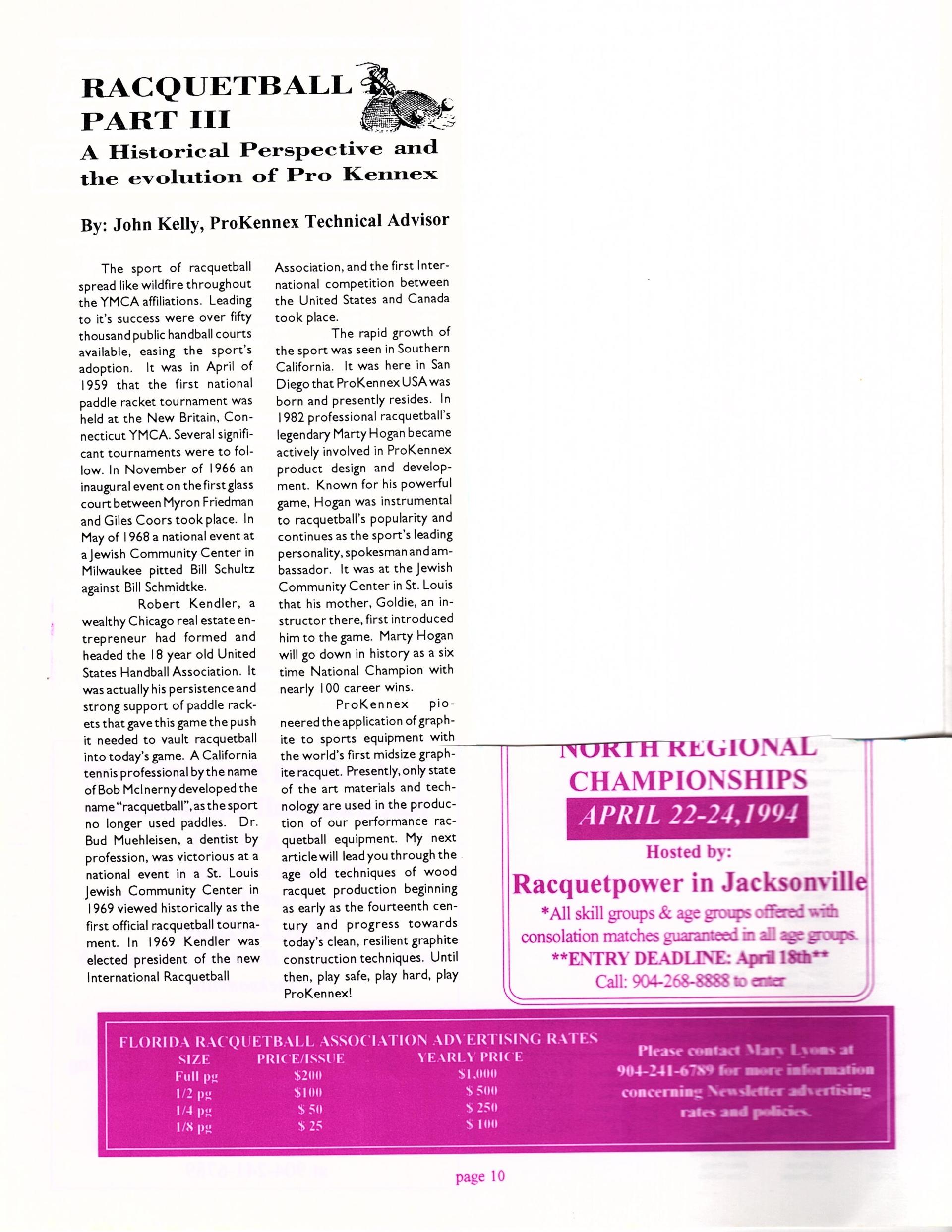

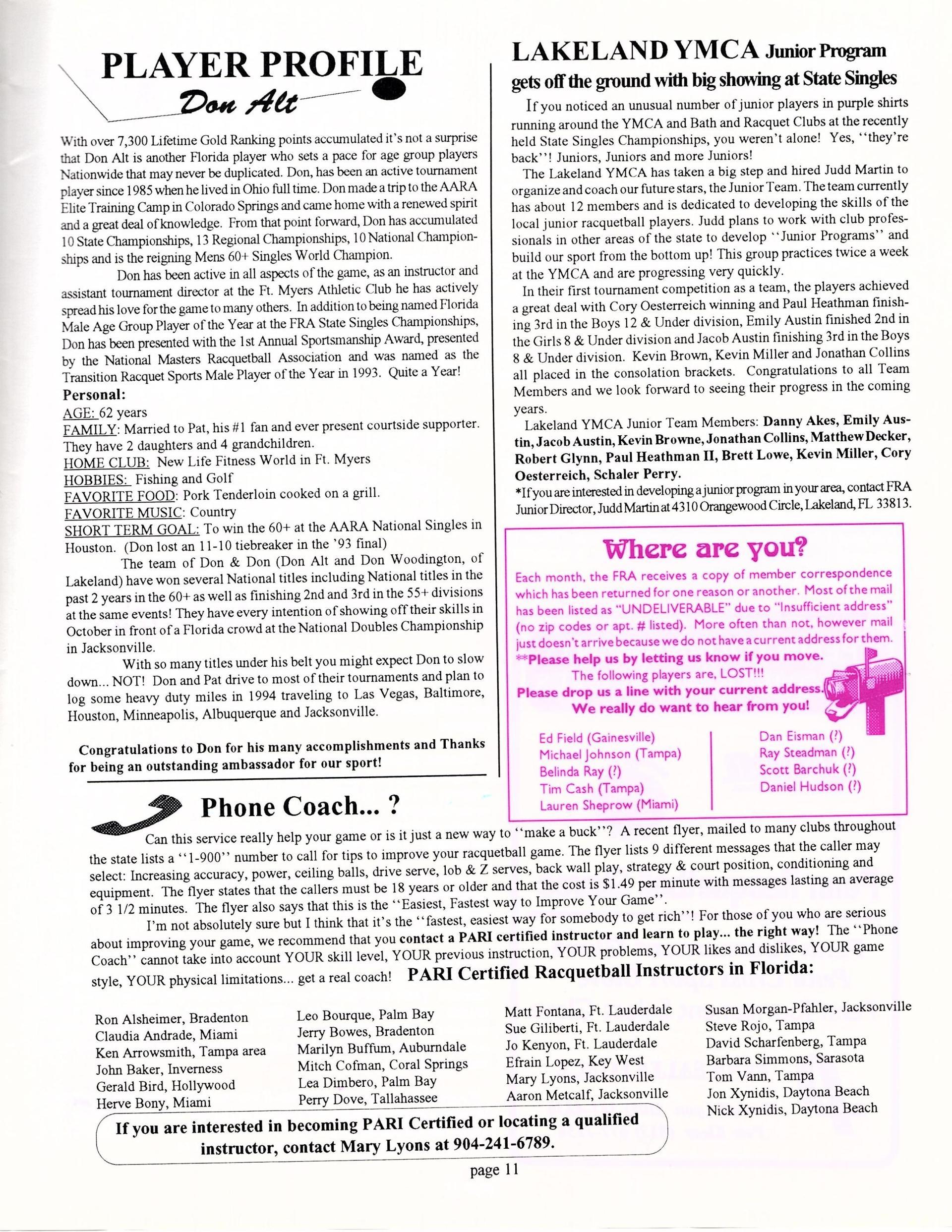

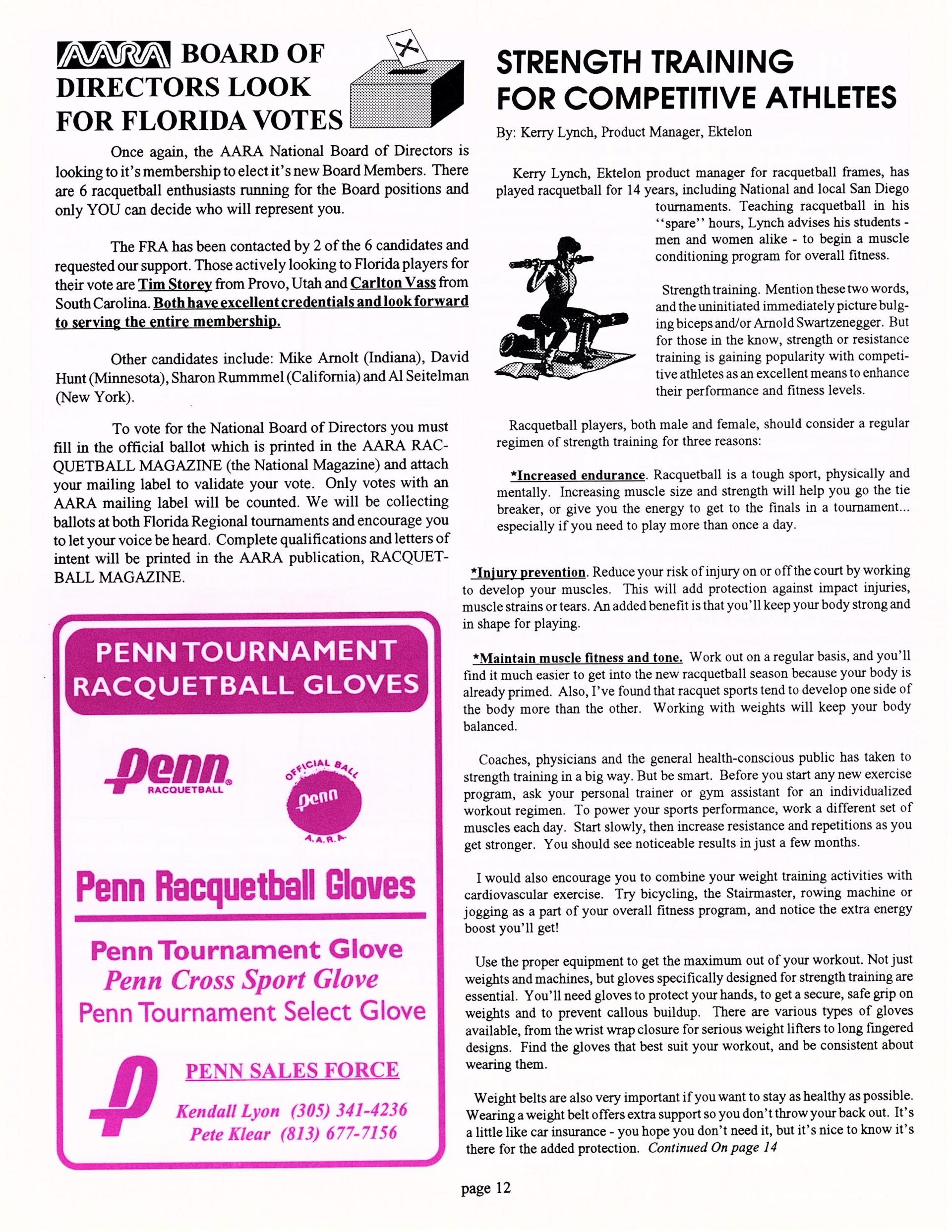

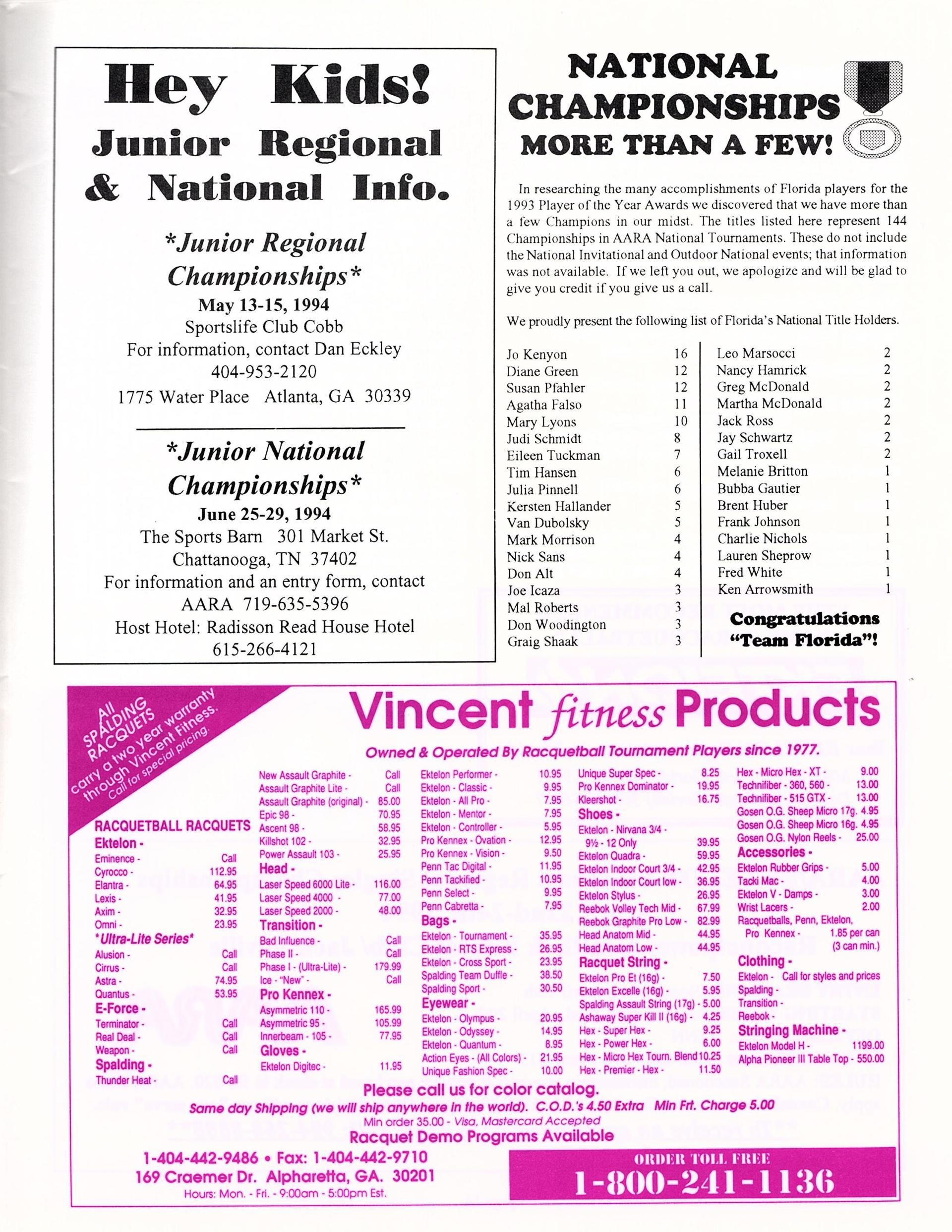

1994

March

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

September

1994 - Drew Kachtik vs Cliff Swain, IRT (Minneapolis)

1993

March

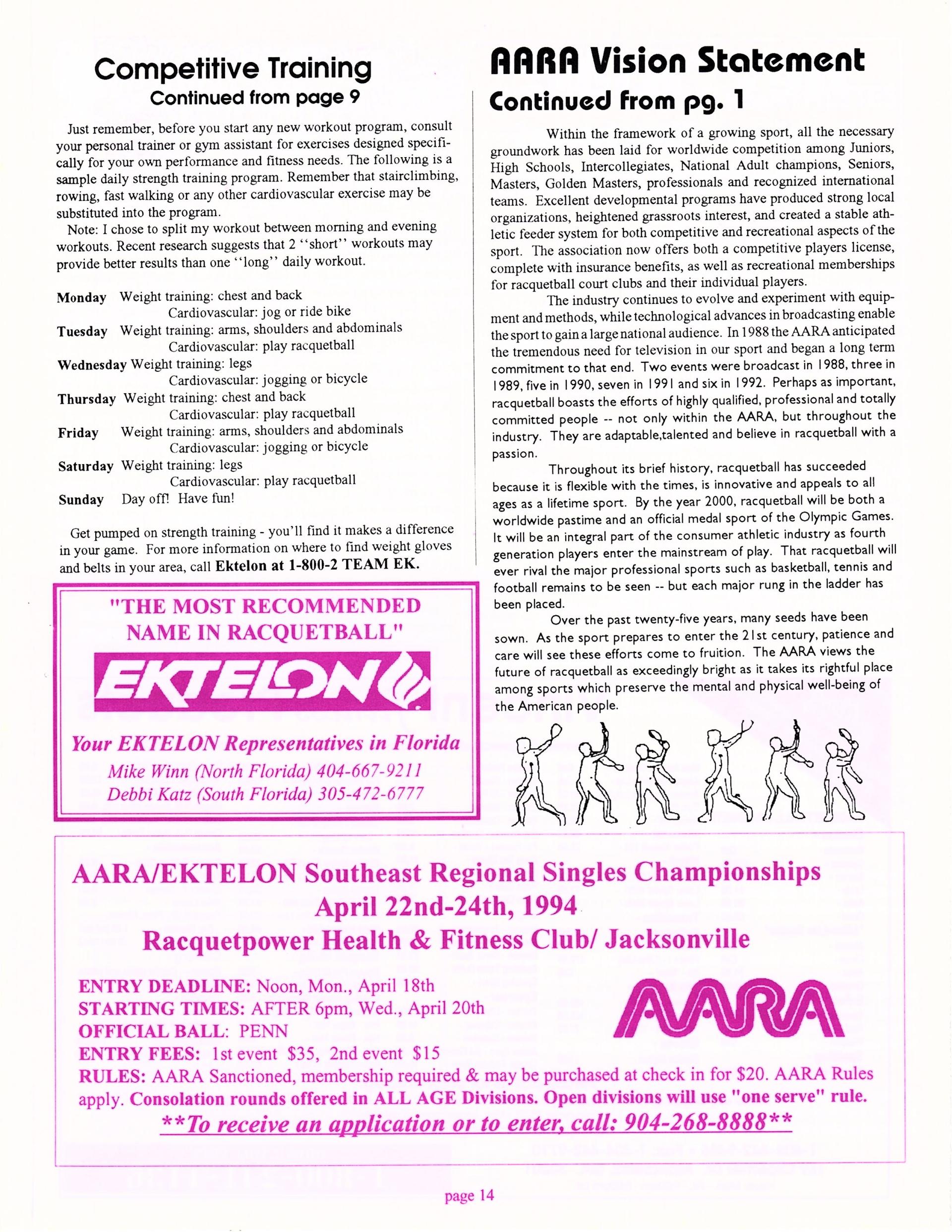

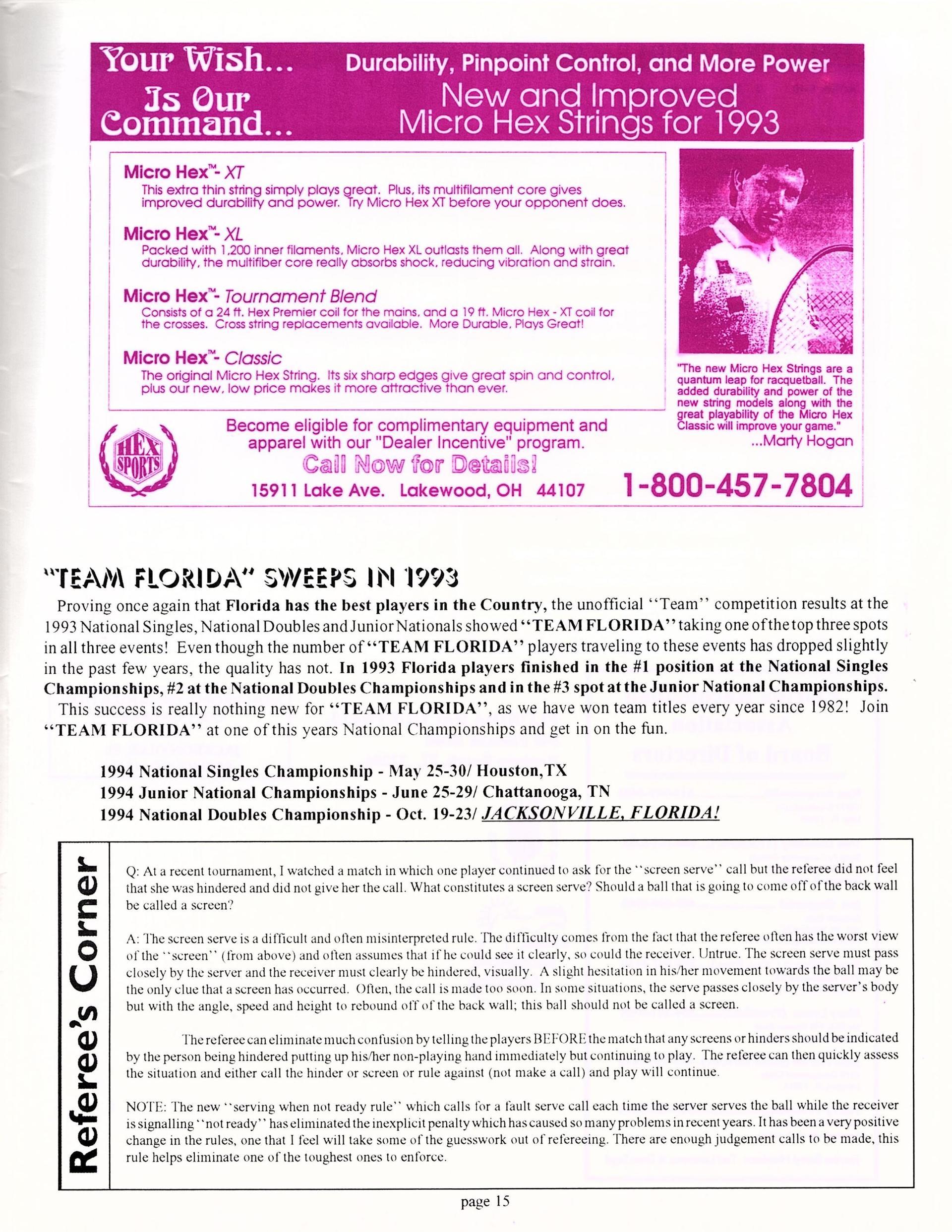

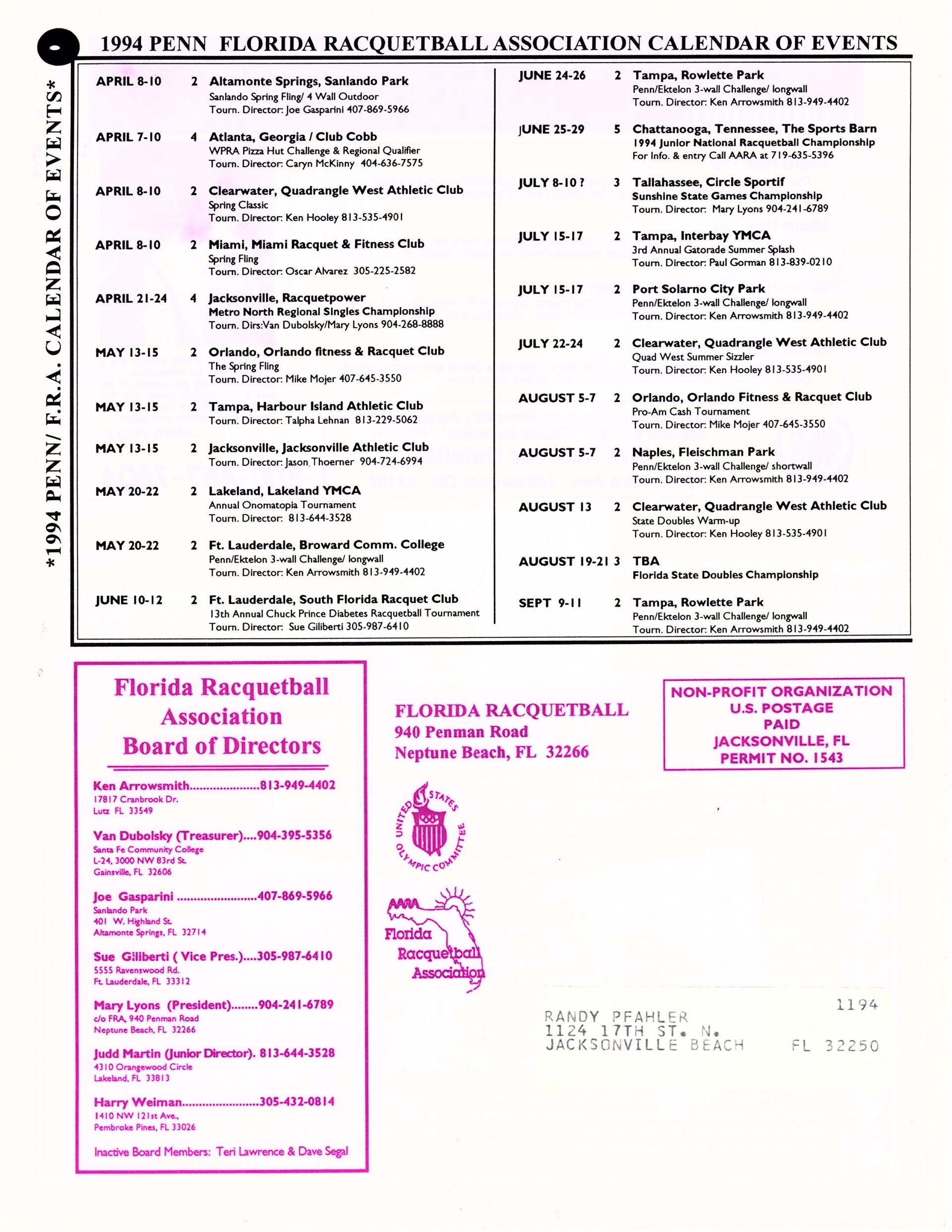

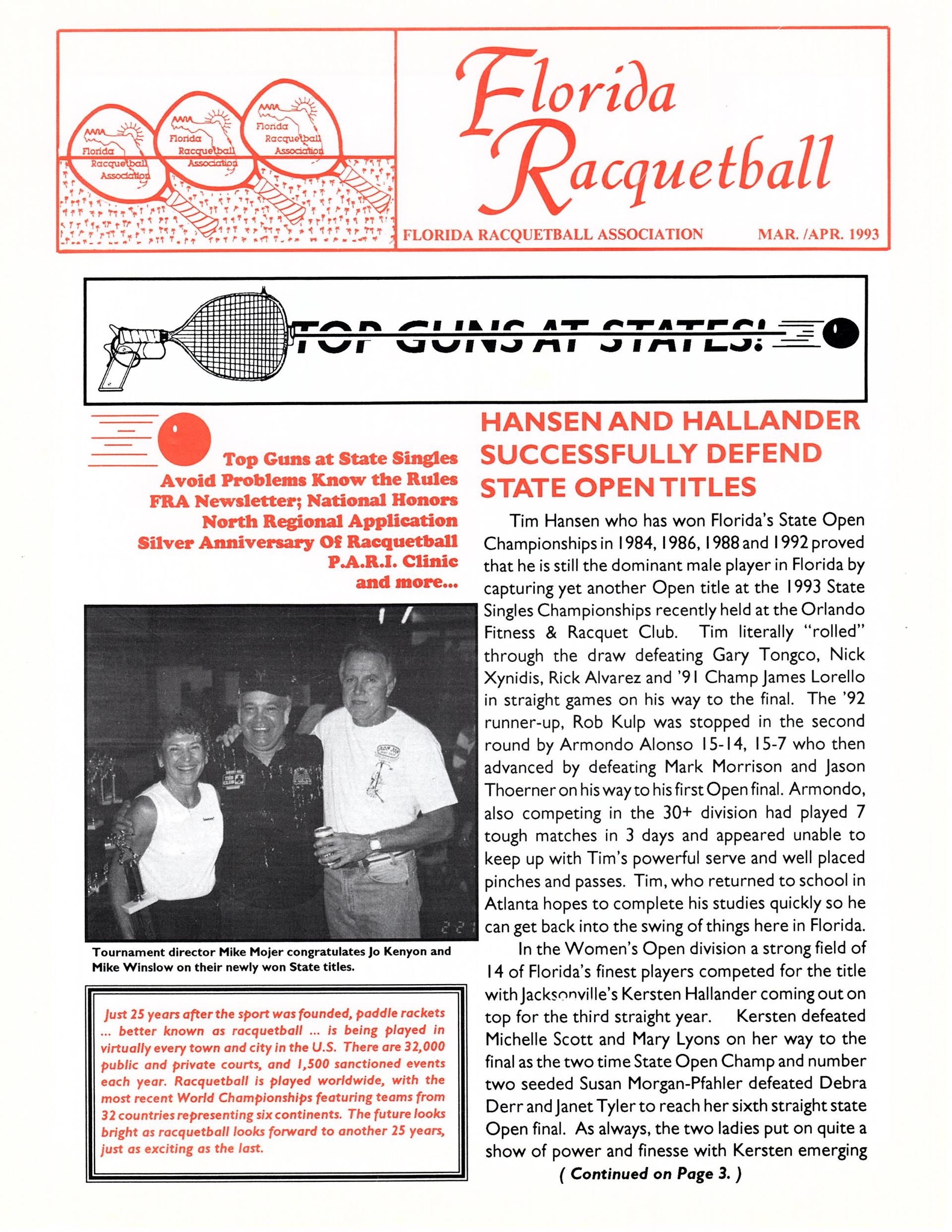

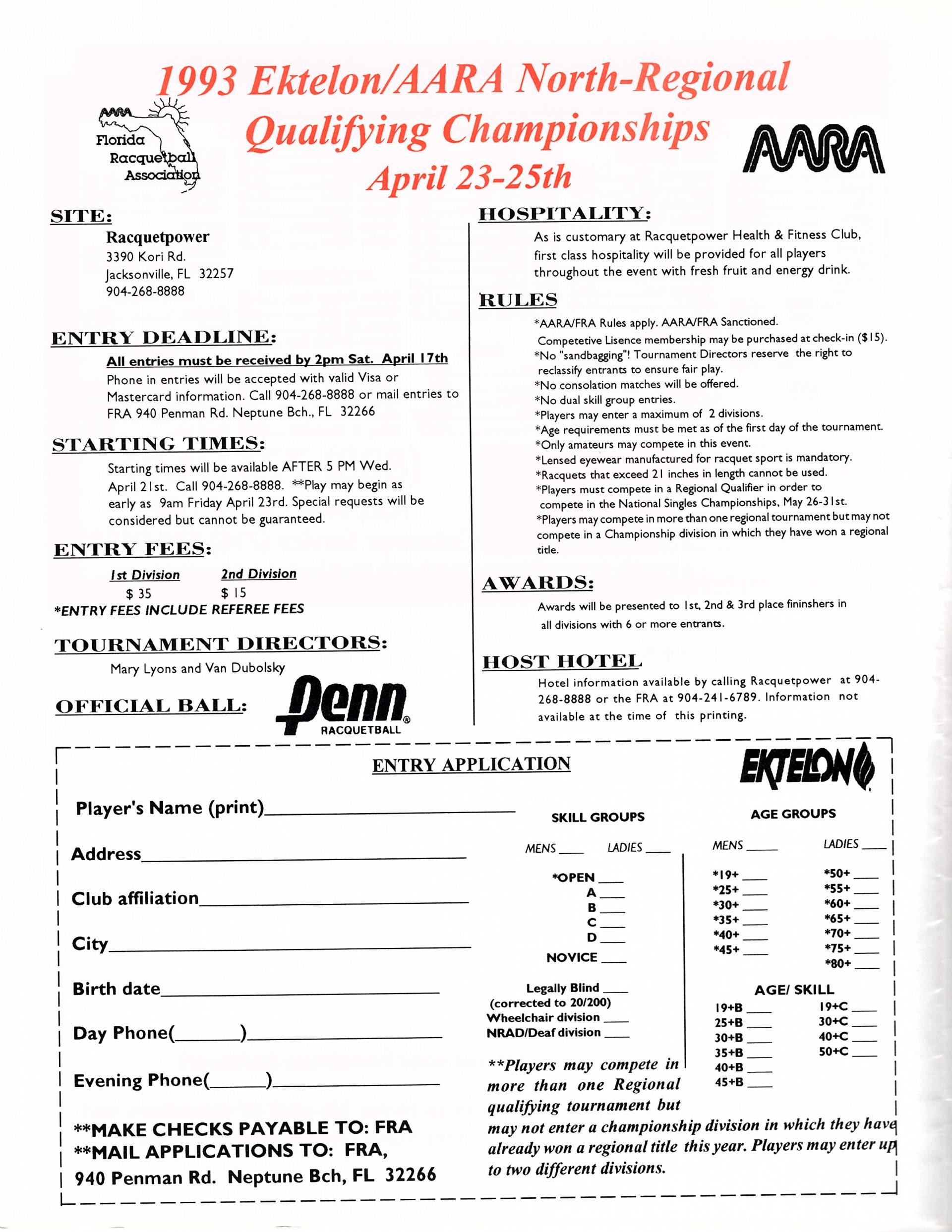

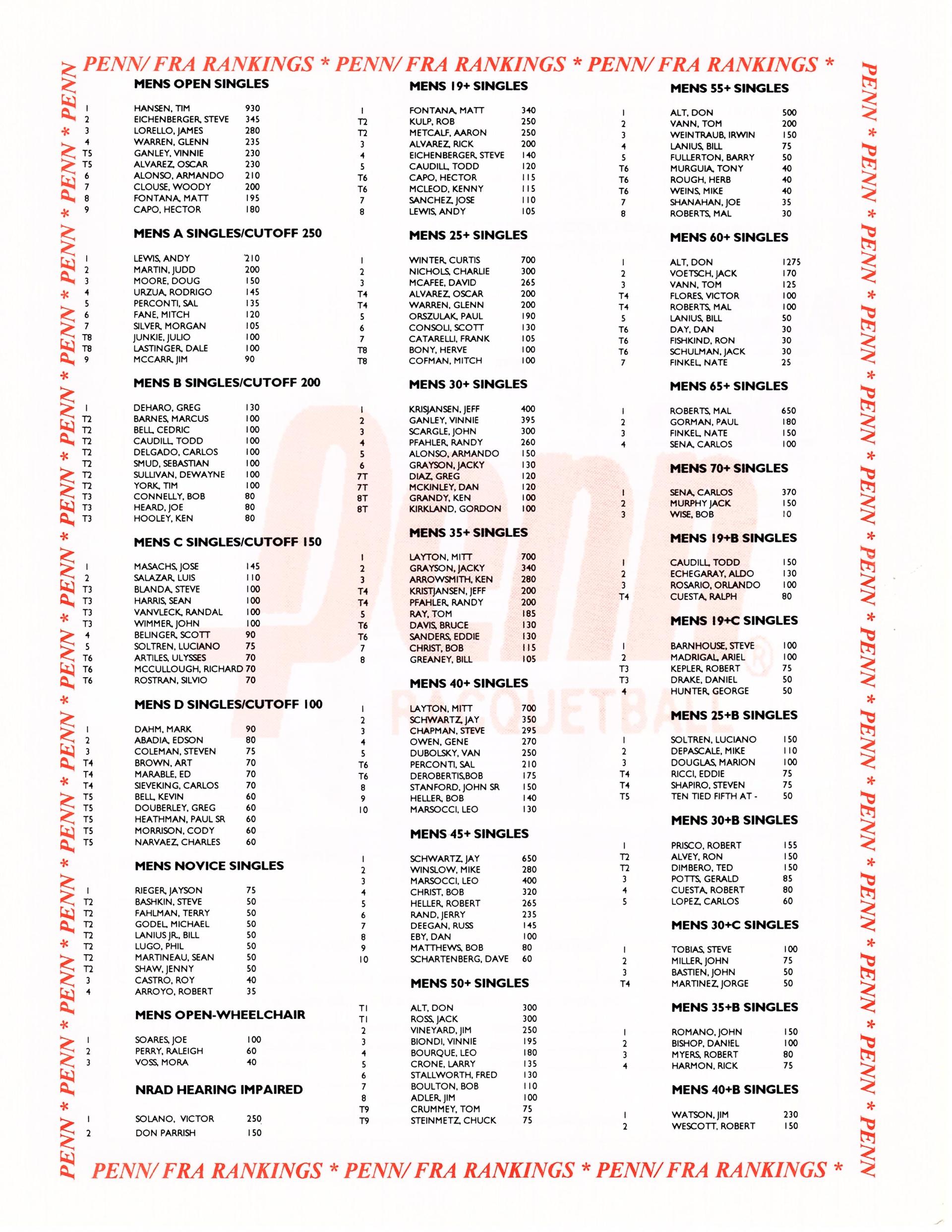

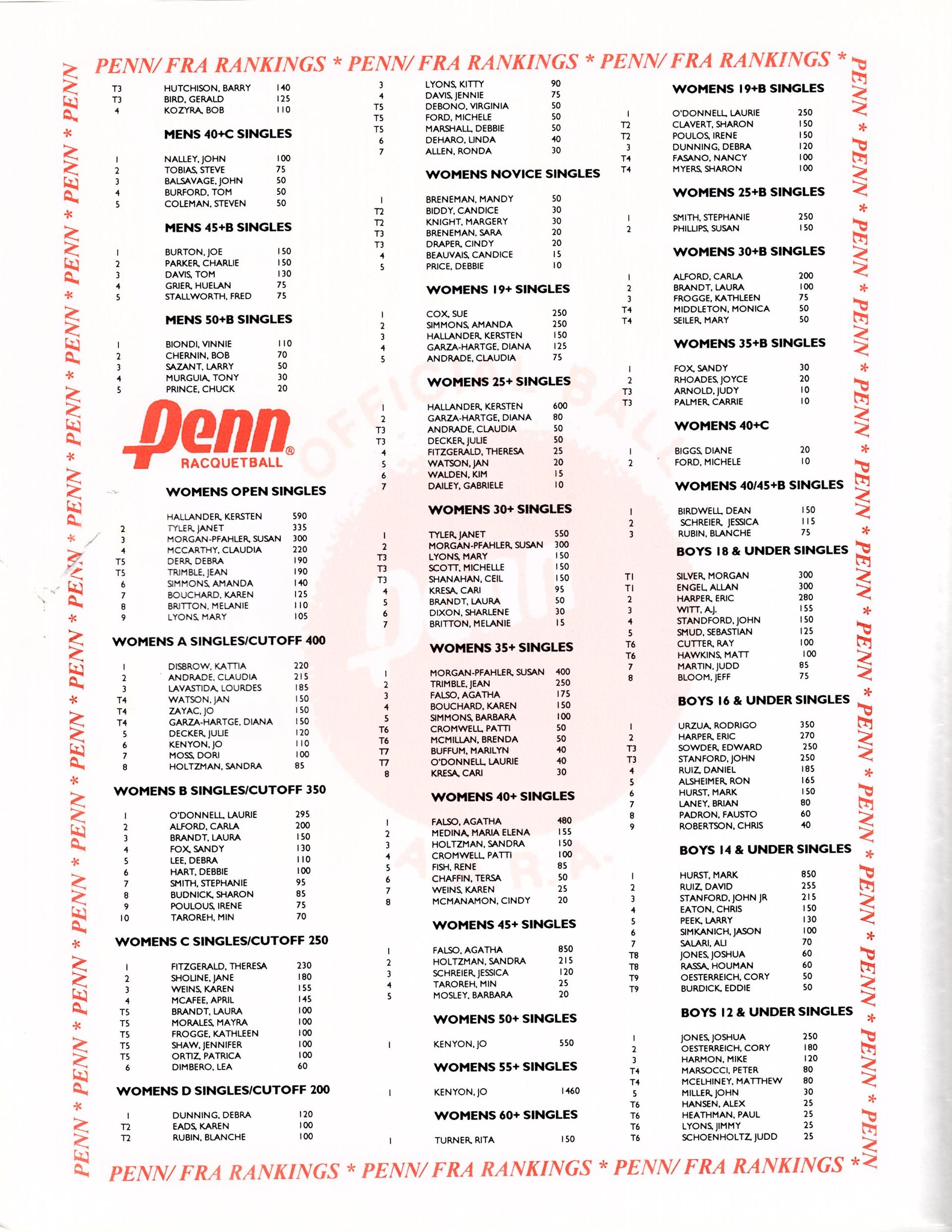

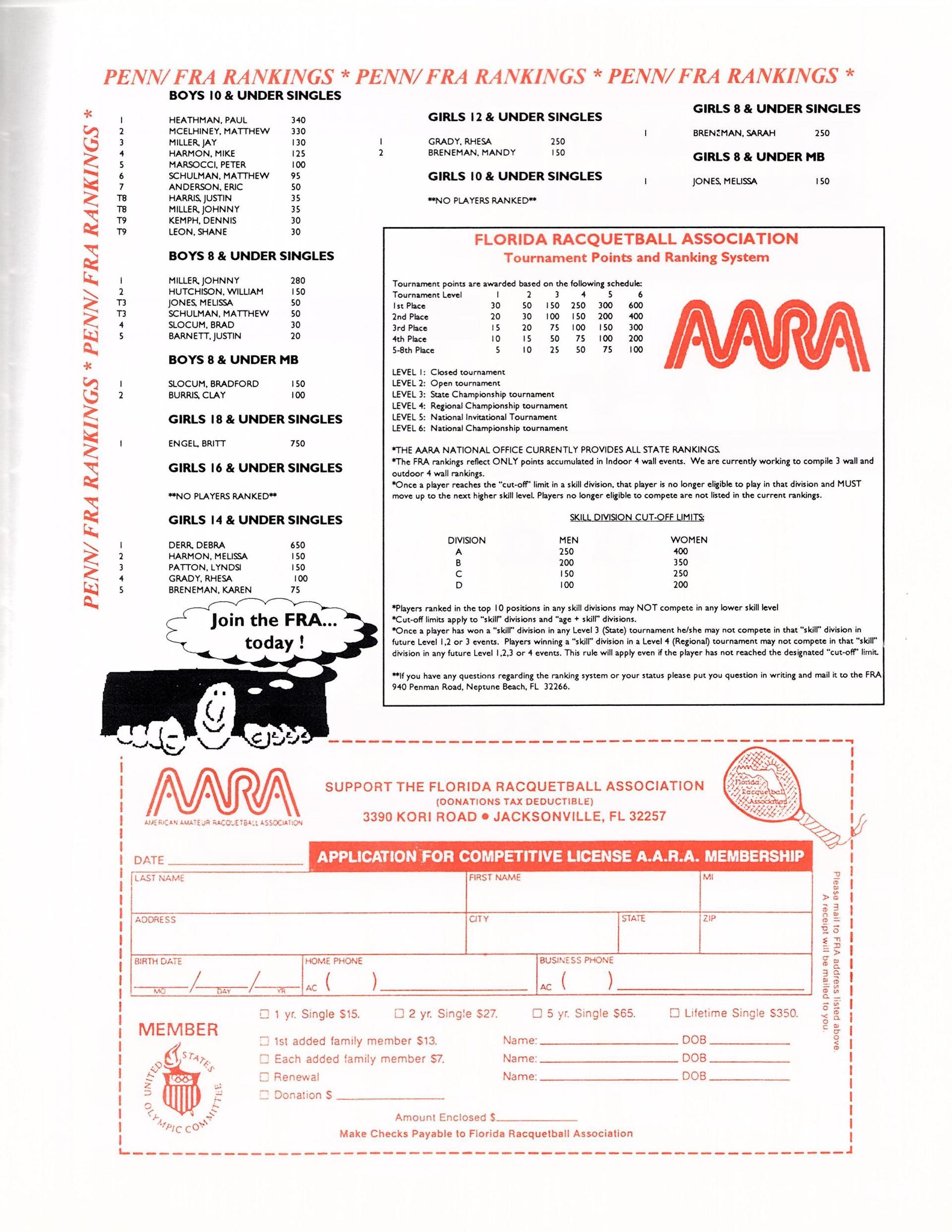

Slide title

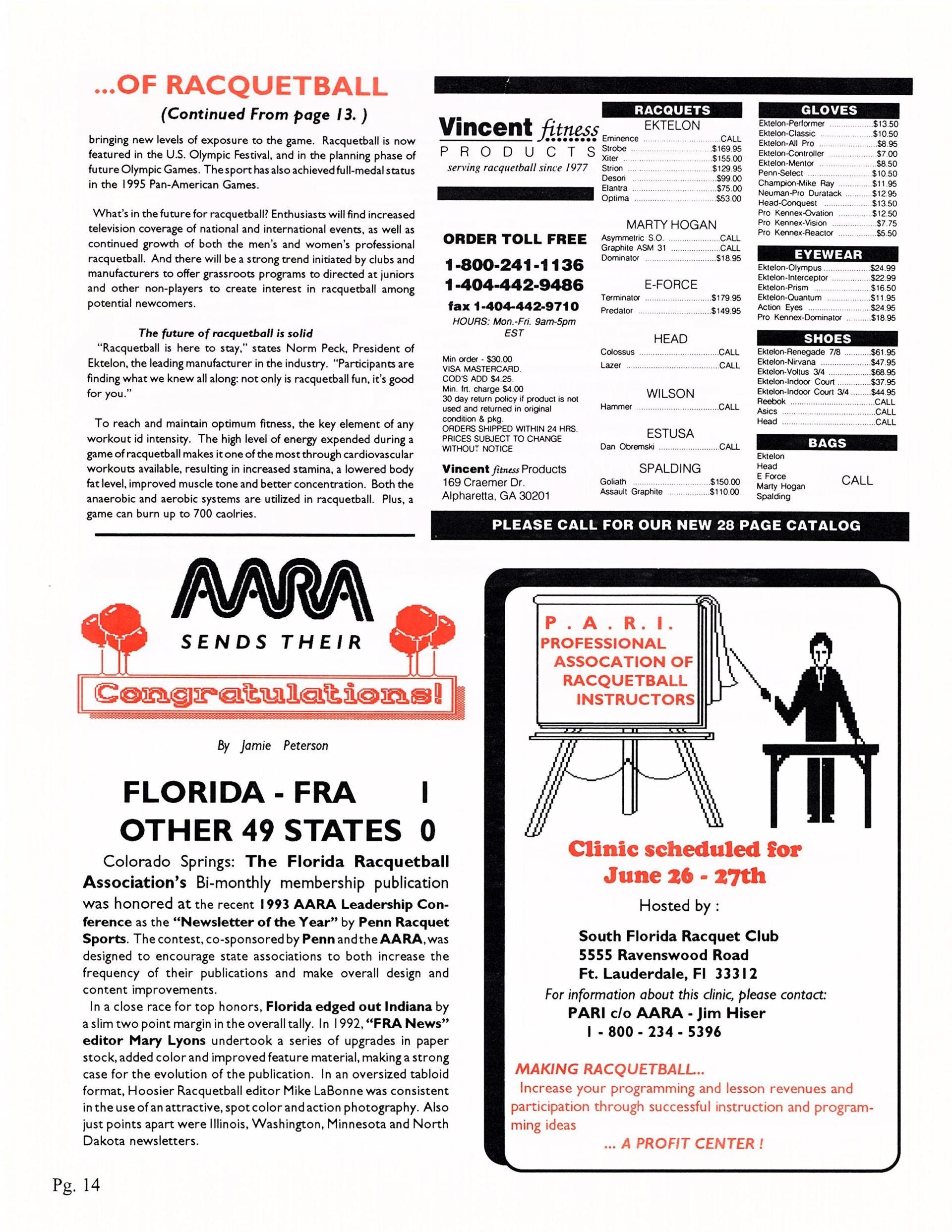

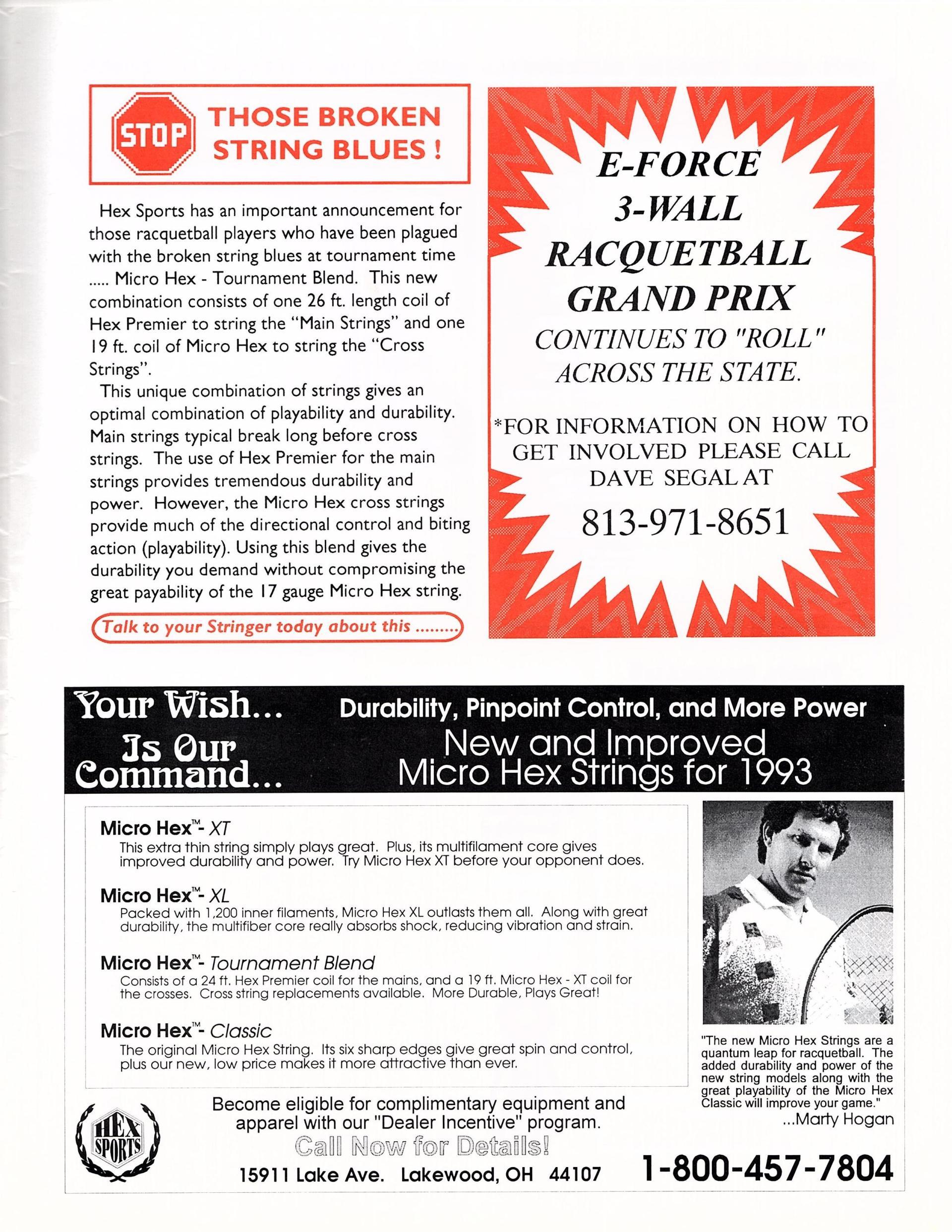

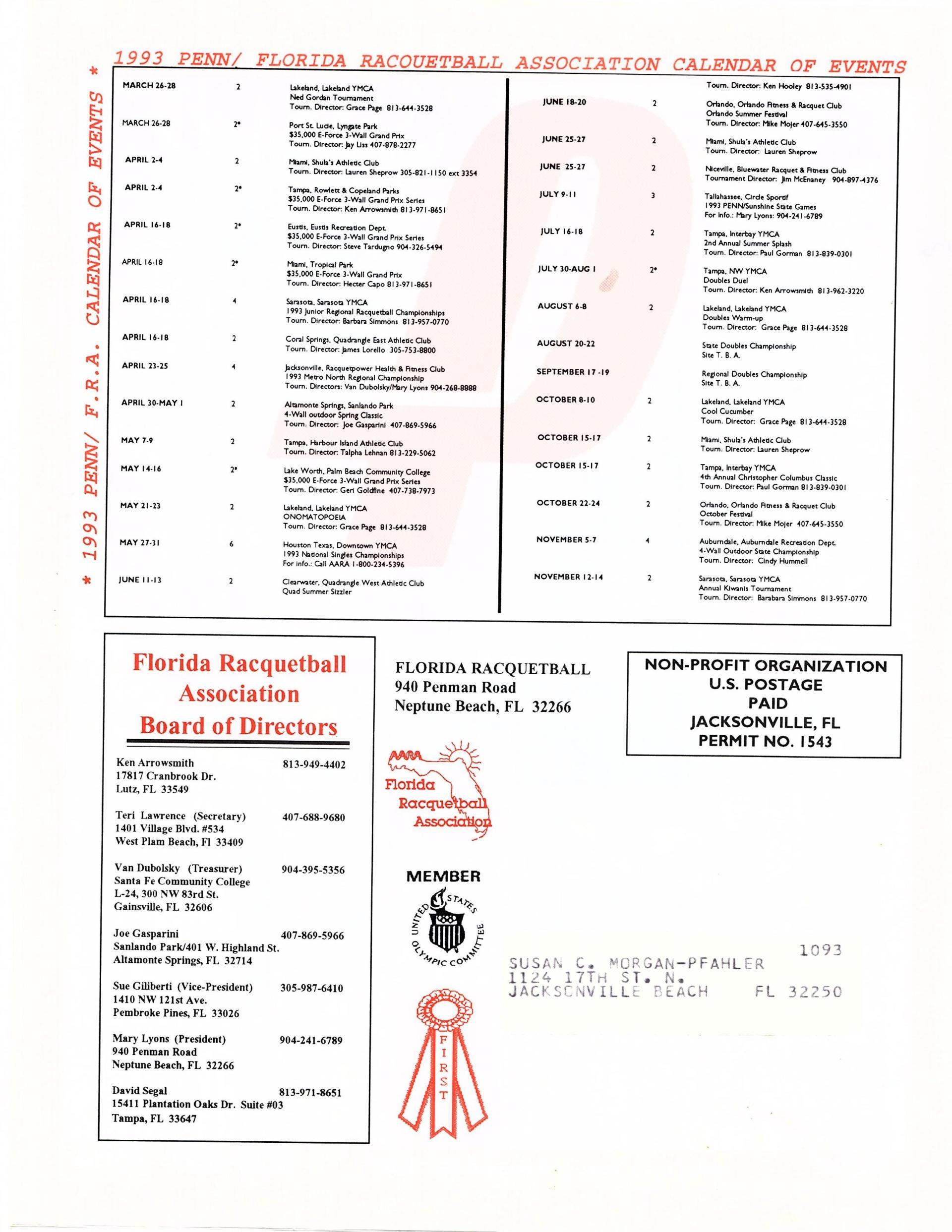

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 1

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 2

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 3

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 4

Button

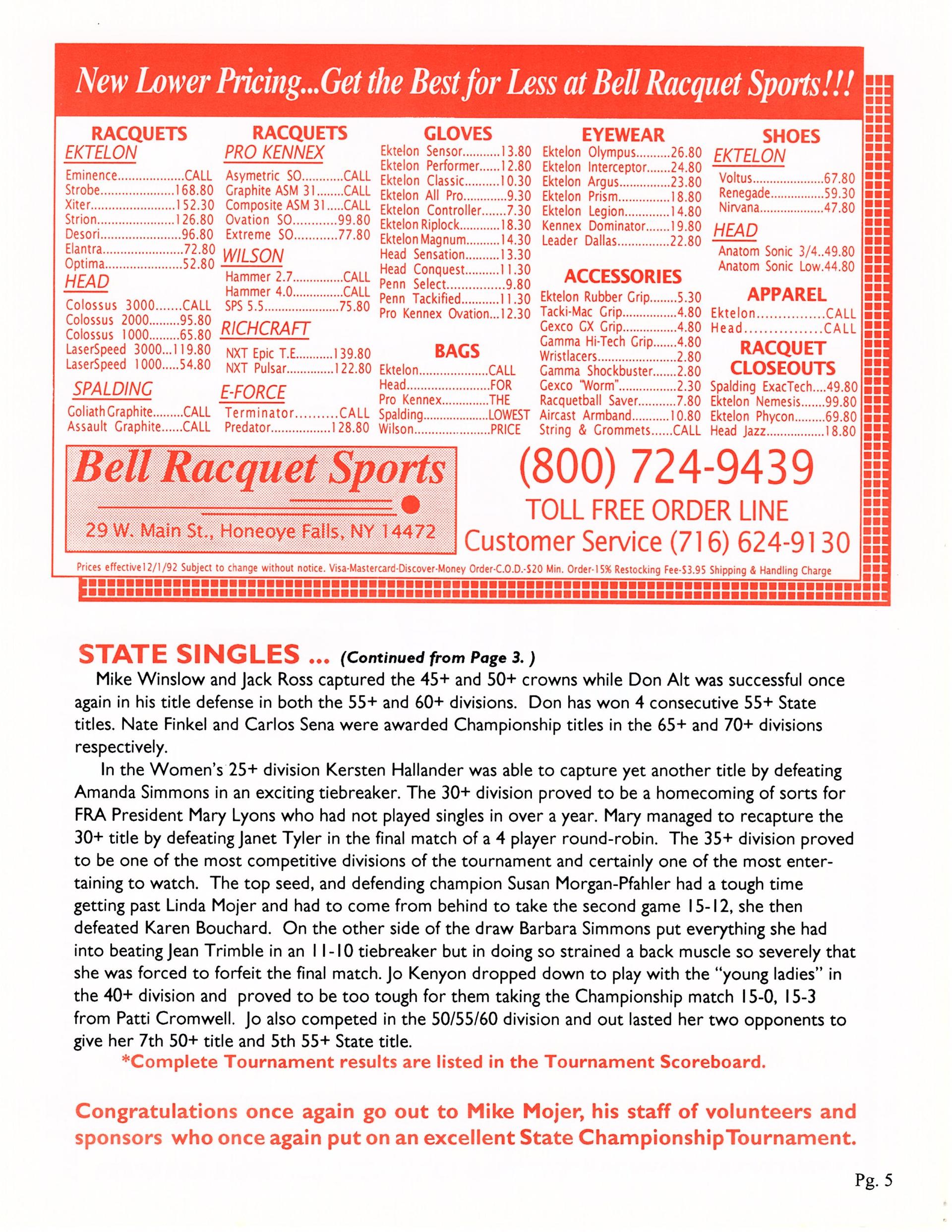

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 5

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 6

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 7

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 8

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 9

Button

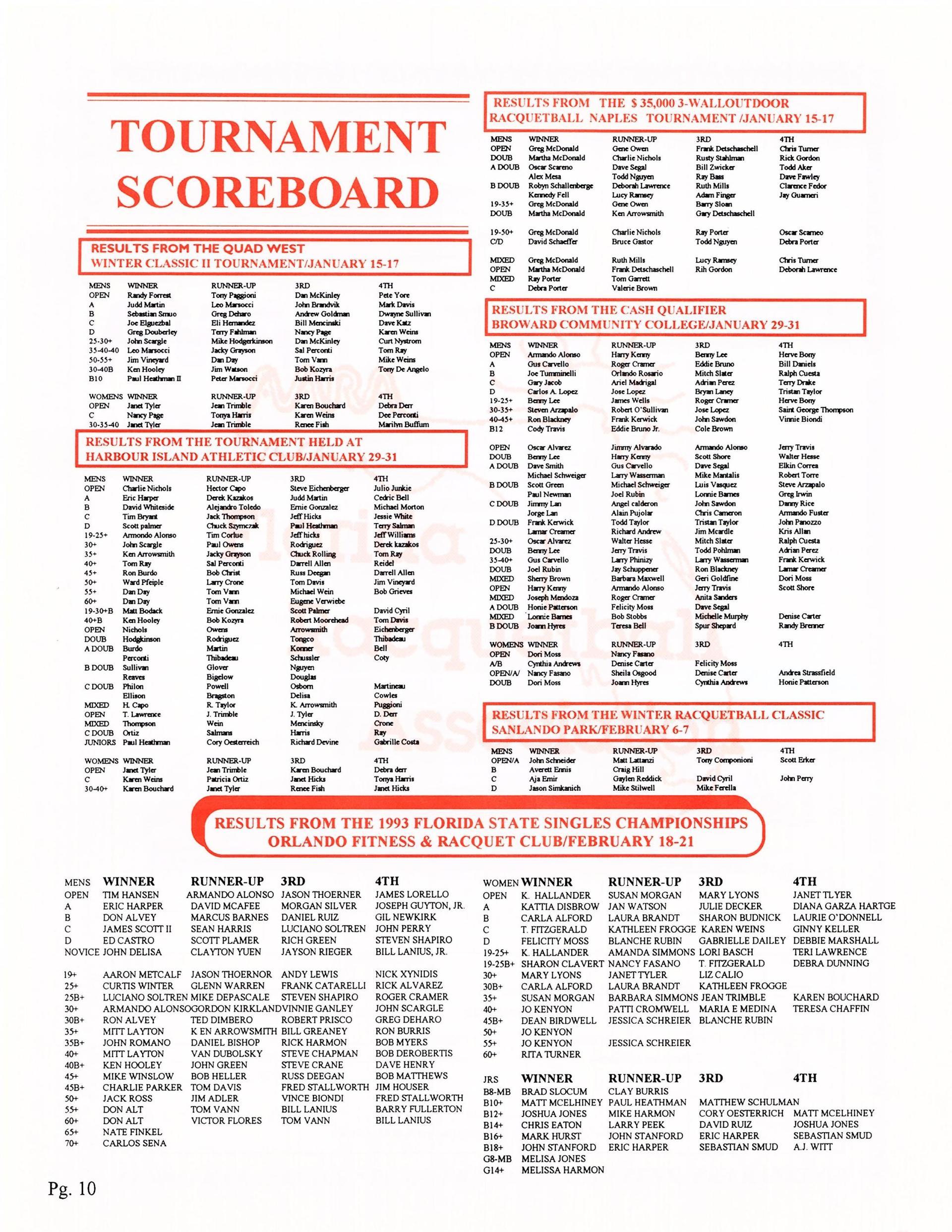

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 10

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 11

Button

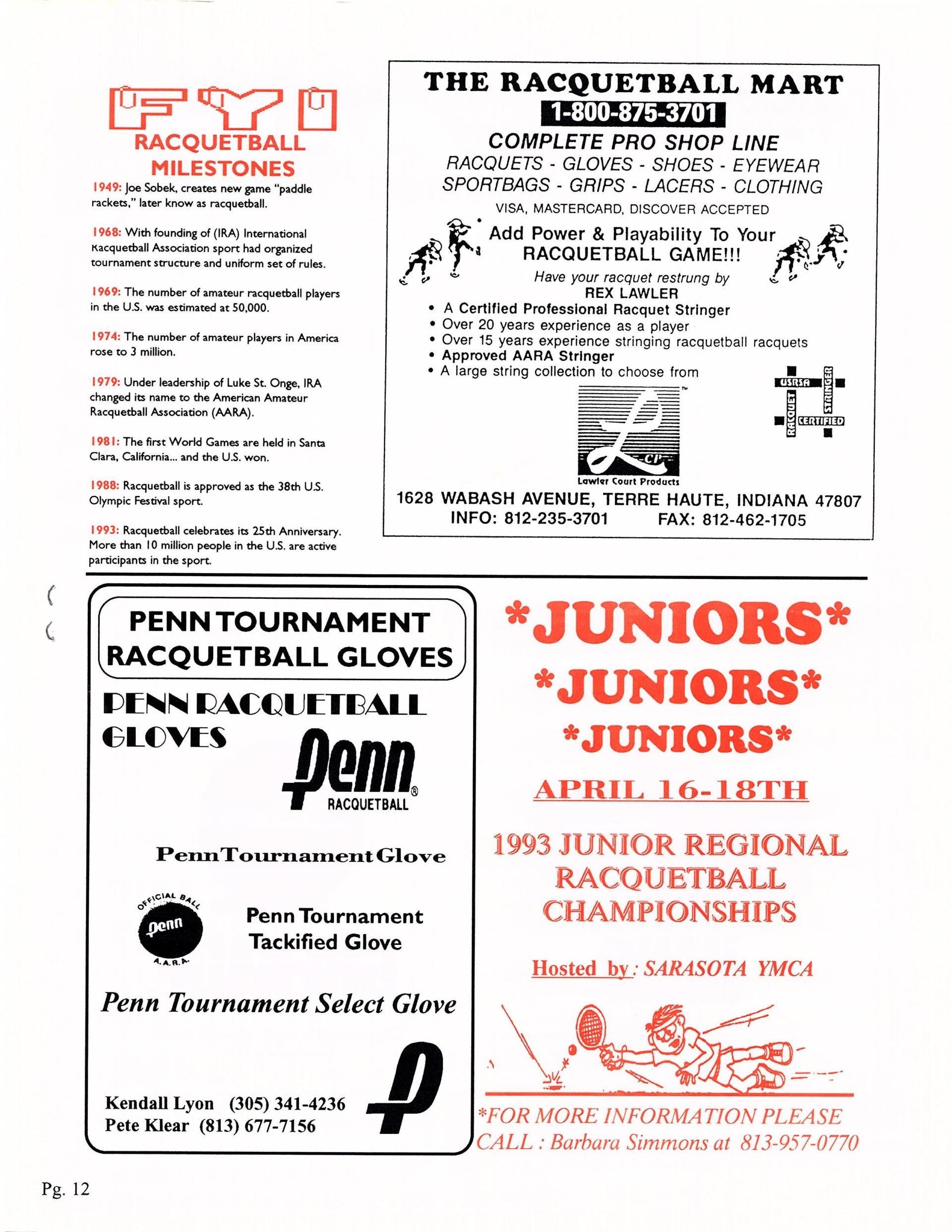

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 12

Button

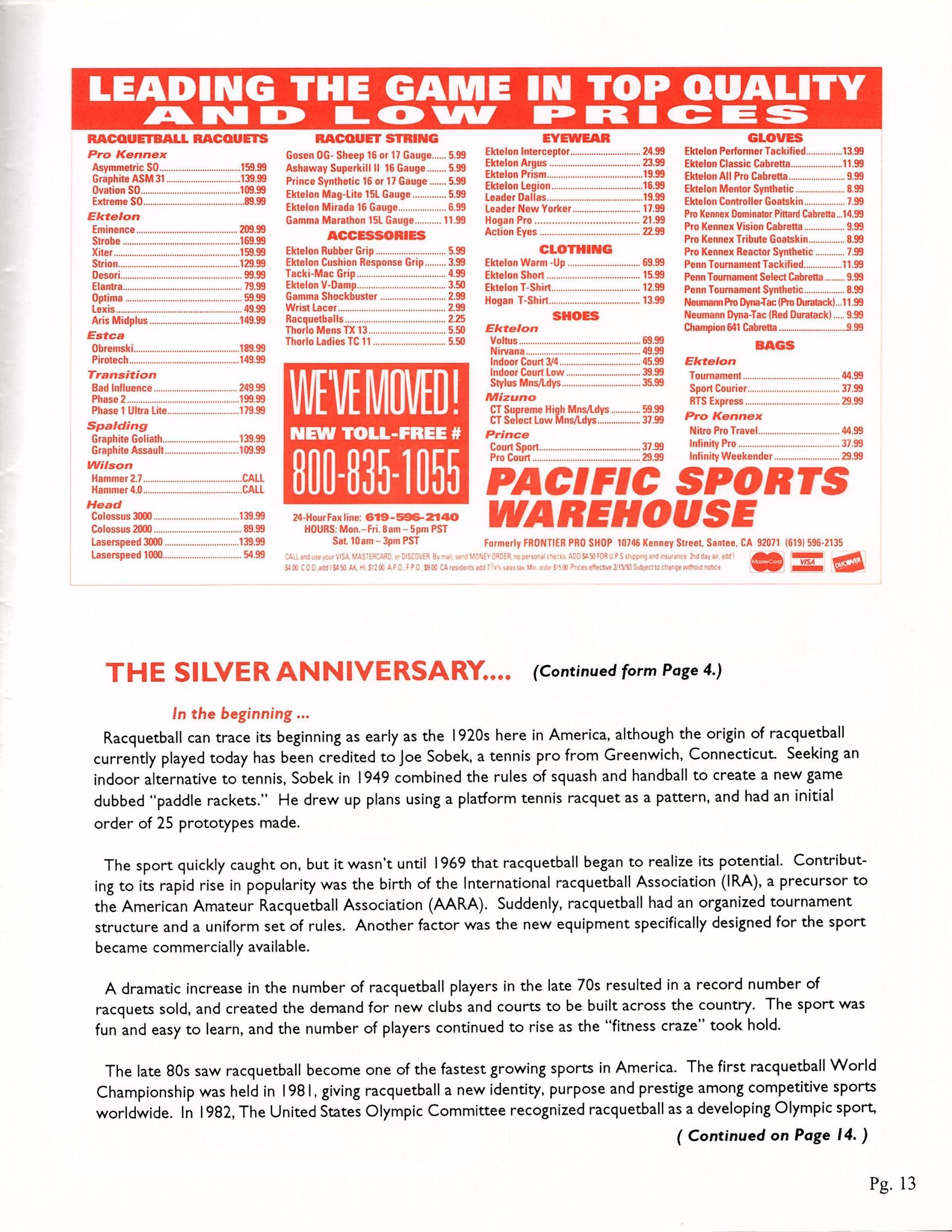

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 13

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 14

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 15

Button

Slide title

FRA Newsletter

Mar/Apr 1993

Page 16

Button

1992

History of Racquetball - 10 Part Documentary

1992 Professional Racquetbhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MpKOwaGiijE&t=35sall - Tim Sweeney vs Cliff Swain (Intro and game 1 of 5)

1992 Racquetball World Championships (2 matches) - 1) Women's Singles - Heather Stupp (Canada)vs Michelle Gould (USA) and 2) Men's Singles - Tim Sweeney (USA) vs Mike Ceresia (Canada)

1991

June

Pacific Rim Championships (Honolulu, HI) - TIm Hansen / Jimmy Floyd (USA) vs Ross Harvey / Mike Ceresia (Canada)

1990

January/February

Download the January/February newsletter for State Singles

June

AT AGE 7, MCELHINEY'S A MASTER

June 23, 1990 | Bradenton Herald, The (FL) - PDF copy of the original article

Author: Tad Reeve, Herald Assistant Sports Editor | Page: C1 | Section: Sports | Column: Speaking of sports

Matthew McElhiney of Bradenton and Jimmy Lyons of Jacksonville battled on the court for more than an hour to

decide the Southeast regional racquetball champion last month.

It was 10-10 in a tense third-game tiebreaker when McElhiney drilled a winner to end the match.

That's when Lyons asked McElhiney to step outside.

Uh-oh.

Sports is filled with potentially volatile situations. Was this one of them? Did Lyons hope to settle the score with

his fists?

Lyons and McElhiney walked to the edge of the parking lot and stood face-to-face for a moment. Then Lyons

stepped toward his rival.\

``Tag,'' he said, ``you're it.''

`Awwww!,'' McElhiney groaned, dodging one car, then another in pursuit of Lyons.

McElhiney is seven years old; Lyons is eight. But, believe me, both play a mean game of racquetball.

Matthew begins play in the Junior National Racquetball Championships today in Dallas. He was fifth in the

tournament's 8-under division last year. Winning it all this time around is not out of the question. He currently is

ranked No. 2 in the nation in 8-under.

McElhiney may be the next racquetball champion in this a town that has built a reputation over the last five years

for producing racquetball champions.

Allan Engel currently sits on that throne. Not surprisingly, Engel, 17, who will be a senior at Manatee High School in the fall, is McElhiney's hero. A four-time national junior champion and the 1990 state open winner, Engel spends several afternoons a week practicing with Matthew.

``I can beat him,'' Matthew said of Engel.

Well, sort of.

When McElhiney and Engel play, they play by Matthew's rules, which means he gets as many bounces as

necessary to hit the ball before it crosses the service line. It's called ``no-bounce'' or multi-bounce'' in racquetball

and it is the rule many 8-under tournaments play by.

Engel is allotted his one bounce.

``I hit the ball as hard as I can and he gets to every shot,'' Engel said. ``He runs me all over the place. He's got

tons and tons of potential.''

Matthew first picked up a racquet at the age of four.

He tagged along with his parents, Ralph and Donna McElhiney, both teachers, during their workouts at a local

fitness center.

``It was kinda boring just sitting around the club not doing anything,'' Matthew said. So he picked up a nearby

racquet.

He played his first tournament at age five and finished fourth that year in the Orange Bowl, which racquetball

considers its world championships.

Last time he played his father, who himself is an accomplished player on Florida's adult beach volleyball circuit,

Matthew won, 15-5.

The kid can play.

But should he compete?

``As long as he likes it, as long as he's having a good time, then it's all right with me,'' says his father. ``I don't see

him as a future Olympian or anything. That stuff doesn't matter to us. As long as he has people like Allan around

him, then I think this is good for him.''

``I don't think anybody is too young to develop a competitive attitude,'' Engel said. ``Competition teaches you a

lot about life, about how to win and how to lose.

``I've been competing since I was nine. I see a lot of myself in him.''

And nothing but good can come of that.

McElhiney, Engel and Cassie Peirce are the three Manatee County representatives playing in Dallas.

Engel, still eligible to play in the 16s, instead has moved up to the 18s, where the tournament champion earns a

spot on the men's national team. That translates into a year's worth of all-expenses-paid travel to tournaments

around the world.

1990 Men's Open State Singles Champion, Allan Engel - The Bradenton Herald - 23 Jun 1990

1990 US Racquetball National Championships Mens Singles Final - Egan Inoue vs Tim Doyle