1970s

1970s

1979

Bill Murray Racquetball Story - Miami, 1979

On this date in 1979...

...The Stars Came Out for Juvenile Diabetes

WTVJ's Bob Lawrence reports on a charity racquetball tournament for the benefit of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation at the Kendall Racquetball & Health Club in this story.

Among the celebs smacking the ball around were WTVJ's own Diana Gonzales, the Miami Dolphins Starbrites and Bill Murray, famous for "Saturday Night Live" (and maybe "Meatballs," released a few months earlier) but not yet famous for "Caddyshack," "Tootsie," "Ghostbusters," "Groundhog Day" and many projects too numerous to mention.

Murray, star of an NBC hit show, mugs for WTVJ's (CBS) camera and makes a cute, network-TV related joke. There's no footage of him playing racquetball, which is a bit of a disappointment.

Subscribe to the Lynn and Louis Wolfson II Florida Moving Image Archives’ YouTube channel and tune in to the fascination and fun of Miami and Florida’s past, captured on film and video and preserved by the Wolfson Archives at Miami Dade College.

This video and audio is copyrighted/owned by the Lynn and Louis Wolfson II Florida Moving Image Archives at Miami Dade College.

This clip is derived from news film in the WTVJ Collection. Accession number 207-02; airdate October 4, 1979.

1979 Nationals

Women's Professional Racquetball Tempe, Arizona

1979 Men's Pro Nationals

Tempe, AZ

1978

February

April

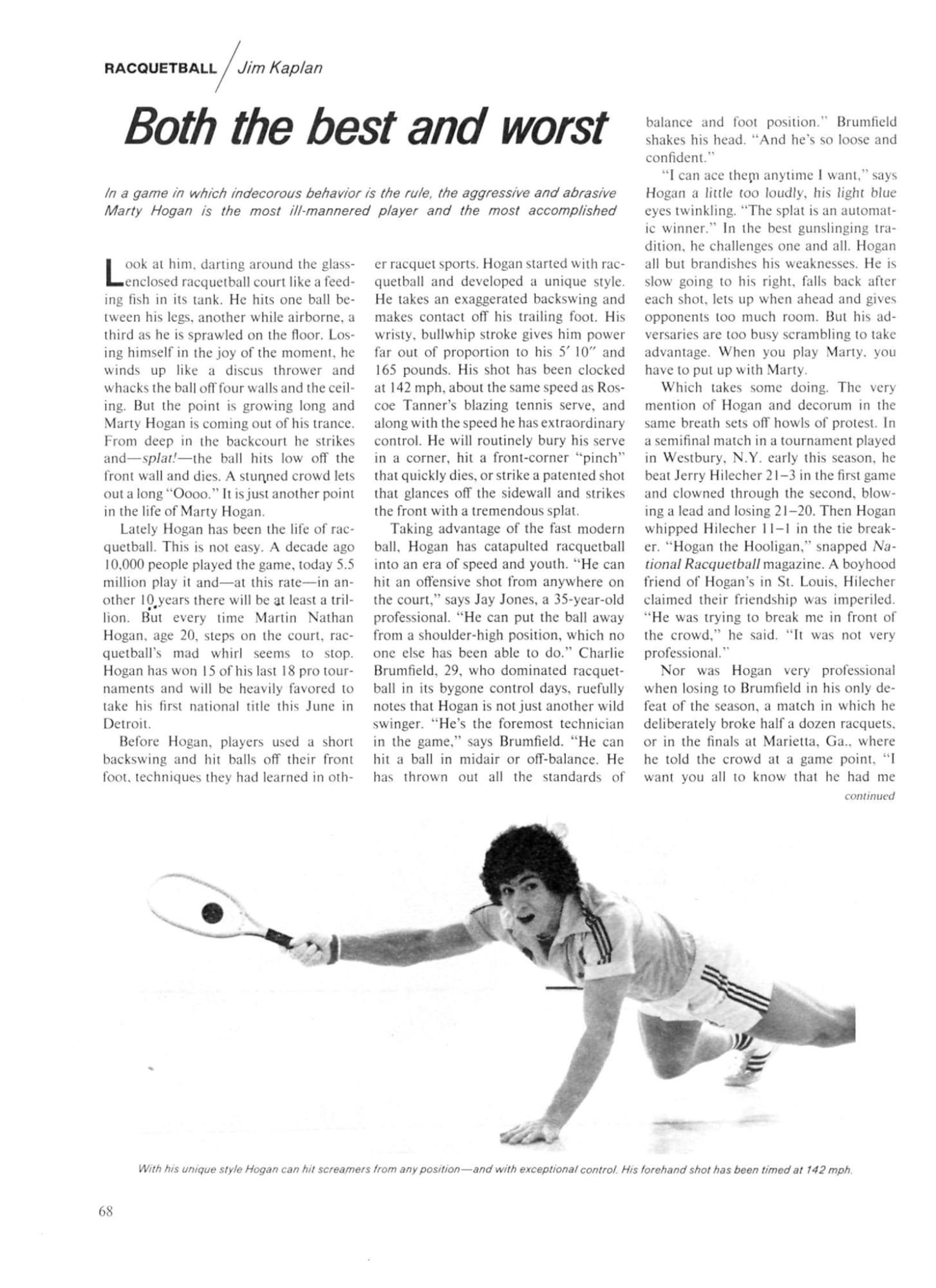

BOTH THE BEST AND WORST -

LINK TO ORIGINAL

IN A GAME IN WHICH INDECOROUS BEHAVIOR IS THE RULE, THE AGGRESSIVE AND ABRASIVE MARTY HOGAN IS THE MOST ILL-MANNERED PLAYER AND THE MOST ACCOMPLISHED

By Jim Kaplan, Sports Illustrated

April 10, 1978

Look at him, darting around the glass-enclosed racquetball court like a feeding fish in its tank. He hits one ball between his legs, another while airborne, a third as he is sprawled on the floor. Losing himself in the joy of the moment, he winds up like a discus thrower and whacks the ball off four walls and the ceiling. But the point is growing long and Marty Hogan is coming out of his trance. From deep in the backcourt he strikes and—splat!—the ball hits low off the front wall and dies. A sturmed crowd lets out a long "Oooo." It is just another point in the life of Marty Hogan.

Look at him, darting around the glass-enclosed racquetball court like a feeding fish in its tank. He hits one ball between his legs, another while airborne, a third as he is sprawled on the floor. Losing himself in the joy of the moment, he winds up like a discus thrower and whacks the ball off four walls and the ceiling. But the point is growing long and Marty Hogan is coming out of his trance. From deep in the backcourt he strikes and—splat!—the ball hits low off the front wall and dies. A sturmed crowd lets out a long "Oooo." It is just another point in the life of Marty Hogan.

Lately Hogan has been the life of racquetball. This is not easy. A decade ago 10,000 people played the game, today 5.5 million play it and—at this rate—in another 10 years there will be at least a trillion. But every time Martin Nathan Hogan, age 20, steps on the court, racquetball's mad whirl seems to stop. Hogan has won 15 of his last 18 pro tournaments and will be heavily favored to take his first national title this June in Detroit.

Before Hogan, players used a short backswing and hit balls off their front foot, techniques they had learned in other racquet sports. Hogan started with racquetball and developed a unique style. He takes an exaggerated backswing and makes contact off his trailing foot. His wristy, bullwhip stroke gives him power far out of proportion to his 5'10" and 165 pounds. His shot has been clocked at 142 mph, about the same speed as Roscoe Tanner's blazing tennis serve, and along with the speed he has extraordinary control. He will routinely bury his serve in a corner, hit a front-corner "pinch" that quickly dies, or strike a patented shot that glances off the sidewall and strikes the front with a tremendous splat.

Taking advantage of the fast modern ball, Hogan has catapulted racquetball into an era of speed and youth. "He can hit an offensive shot from anywhere on the court," says Jay Jones, a 35-year-old professional. "He can put the ball away from a shoulder-high position, which no one else has been able to do." Charlie Brumfield, 29, who dominated racquetball in its bygone control days, ruefully notes that Hogan is not just another wild swinger. "He's the foremost technician in the game," says Brumfield. "He can hit a ball in midair or off-balance. He has thrown out all the standards of balance and foot position." Brumfield shakes his head. "And he's so loose and confident."

"I can ace them anytime I want," says Hogan a little too loudly, his light blue eyes twinkling. "The splat is an automatic winner." In the best gunslinging tradition, he challenges one and all. Hogan all but brandishes his weaknesses. He is slow going to his right, falls back after each shot, lets up when ahead and gives opponents too much room. But his adversaries are too busy scrambling to take advantage. When you play Marty, you have to put up with Marty..

Which takes some doing. The very mention of Hogan and decorum in the same breath sets off howls of protest. In a semifinal match in a tournament played in Westbury, N.Y. early this season, he beat Jerry Hilecher 21-3 in the first game and clowned through the second, blowing a lead and losing 21-20. Then Hogan whipped Hilecher 11-1 in the tie breaker. "Hogan the Hooligan," snapped National Racquetball magazine. A boyhood friend of Hogan's in St. Louis, Hilecher claimed their friendship was imperiled. "He was trying to break me in front of the crowd," he said. "It was not very professional."

Nor was Hogan very professional when losing to Brumfield in his only defeat of the season, a match in which he deliberately broke half a dozen racquets, or in the finals at Marietta, Ga., where he told the crowd at a game point, "I want you all to know that he had me 14-6 and now it's 20-14 my lead." But the crusher came in Westminster, Calif. when he cursed and raged at Davey Bledsoe, his opponent in the finals.

As unseemly as Hogan's behavior may be, many of his peers say it must be viewed in context. Hogan's braggadocio gives him a competitive edge, they say, and his tantrums provide timely release. Moreover, the consensus is that Hogan means little harm. "He just has a great will to win at all cost," says Bledsoe. Others point out that Hogan is usually a considerate opponent, given to calling errors on himself. "He's the fairest player on the tour," says Jones.

Even Hogan's critics acknowledge that he is more immature than malicious. Leading a match, he will clown, mug, laugh at himself, make melodramatic gestures or even play serious racquetball. It is for the most part harmless, if bad-mannered, entertainment. But let a match get close and his racquet may fly.

One man who might be able to restrain Hogan, if only he wanted to, is Charlie Drake, the chief executive officer of Leach Industries, the game's major manufacturer. Drake's company has contractual arrangements with so many players that he can often leave a tournament before the semis, knowing a client will win. Hogan lives at Drake's beachfront home in La Jolla, Calif., and Drake is his business manager and closest adviser. Some feel Drake actually encourages Hogan's rowdiness, and Drake does not exactly deny it. "People have become much more comfortable with emotion," he says. "I hate to stifle creativity and Marty's a natural, creative person. It's just that he's incredibly sensitive."

Drake believes Hogan would have won the 1977 nationals if he had unleashed his emotions. "His mother and grandmother were in the front row, and when things got tight he didn't have his usual outburst," Drake says. "So Bledsoe, who was playing very well, upset him." This year, Drake promises, the outcome will be different. "If I was to play doctor," he says, "I would have his family there, but not in the front row."

"Bledsoe was very lucky," says Hogan. "There won't be any flukes this time." Pronouncing himself bored with all the controversy, he adds, "I don't care. I play the way I want to. I ain't puttin' on no act because some snob wants to see a nice boy. When I'm out there, it's my show." As he finishes, he is laughing.

Sound familiar? Hogan resembles a lot of temperamental athletes, but no one so much as Jimmy Connors. Hogan and Connors both grew up in St. Louis, became stars at a young age and had their considerable egos nurtured by protective women—Gloria and his grandmother, the late Two-Mom, in Connors' case; mother Goldie and maternal grandmother Frieda in Hogan's. But even if we don't believe stories of a newer, nicer Jimbo, there is one glaring difference between Connors and Hogan. Connors has been an aberration in tennis; Hogan and racquetball seem to be made for each other.

Tennis, after all, grew out of court, or "royal," tennis, an ancient game that stresses playing form and comportment. Connors' hell-bent style and erratic behavior immediately set him apart. Racquetball evolved from handball, a brutal, often impolitic game brought over by Irish immigrants and dominated until recently by urban Jews. Racquetball is handball's spiritual heir, and Marty Hogan, who happens to be Irish on his father's side and Jewish on his mother's, is its latest prophet.

He grew up around the St. Louis Jewish Community Center, the celebrated "Jay" that is pro racquetball's prime feeder. Hogan's mother, who is separated from her husband and is supporting her family as a locker-room attendant at the Jay, handed Marty his first racquet at age eight. She taught him almost everything he knows about the game, played him until he was too good for her and will accept no criticism of him. "You could search the world over and never find a better boy," she says. Marty is correspondingly loyal, both to Goldie and his more philosophical grandmother Frieda, who calls him "Ho-Ho" Hogan.

For some years Hogan was just another Jay bird. In the 1975 nationals he lost a first-round match to Victor Niederhoffer, a squash champion, of all things. Niederhoffer ad-libbed shots Hogan had never seen and beat him 21-20 in the rubber game on a multiwall squash shot. At this point Hogan realized he would have to take his game beyond the comforts of home and the Jay. He went west that summer, played nearly every day and in the fall knocked off three of the country's top four players in Burlington, Vt. to win his first pro tournament.

The well-protected fledgling then left the nest for good. What kind of society did he fall into? Certainly not a polite one. During a racquetball match every form of psyching is permitted. It is perfectly common, if not ho-hum, to see one player threaten to kill another. Brumfield, the nonpareil hustler, once stuck a racquet under Hogan's chin, pushed him a few inches and threatened to bop him if he didn't back off. Brumfield was penalized one point—and won going away. It was only natural for an impressionable kid like Hogan to take these rough practices to new levels of perfection. His most memorable antics come when the crowd or another player bugs him, which often happens when you are the fastest gun. "Don't get him a little mad," says a tour regular. "The only way to beat him is when he's out of his mind or so lackadaisical he'll showboat."

Most of the time Hogan stays between the extremes. Brumfield believes that as Hogan matures he will lose his nasty edge and be more beatable.

This may be nothing more than another Brumfield psych. Former national champion Bill Schmidtke has a more likely prediction. "Hogan will be on top for a few years," he says, "but there are lots of young kids coming up who can hit just as hard. Sooner or later someone will be able to match him on the high shots."

Meanwhile, in his own words, Hogan is "ridin' high, cruisin', surfin', layin' on the beach lookin' for broads." He attends San Diego State on a scholarship paid for by Leach Industries and maintains a B average, thanks in part to coaching from Drake and Drake's secretary, Patty Reid. There is plenty of time to practice, run the beach with his cherished Dobermans, and drive his van or motorcycle at his customary breakneck speed. Marty mixes well with the locals, and the other players are always saying he is a "fun guy" to be around when he doesn't have a racquet in his hand.

And why shouldn't he be? "He earned $60,000 to $70,000 last year and we are projecting $100,000 for 1978," says Drake. "His income from appearances and endorsements should be 2½ times his purses. He just signed a contract with K Mart that compares favorably with Johnny Miller's deal with Sears."

In other words, Ho-Ho Hogan will be ho-ho-hoing all the way to the bank.

With his unique style Hogan can hit screamers from any position—and with exceptional control. His forehand shot has been timed at 142 mph.

1978 Tanner Pro-Am Women's Pro Final

Shannon Wright vs Peggy Steding

November

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

Slide title

Write your caption hereButton

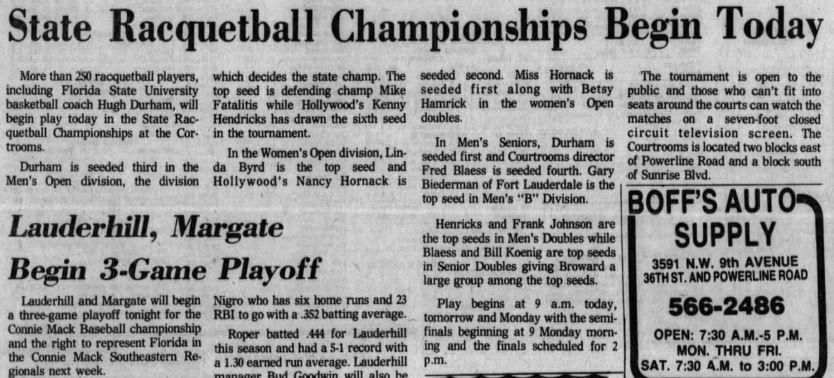

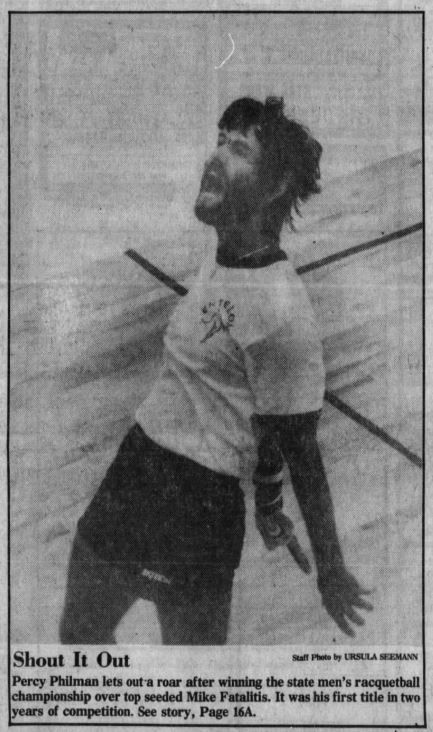

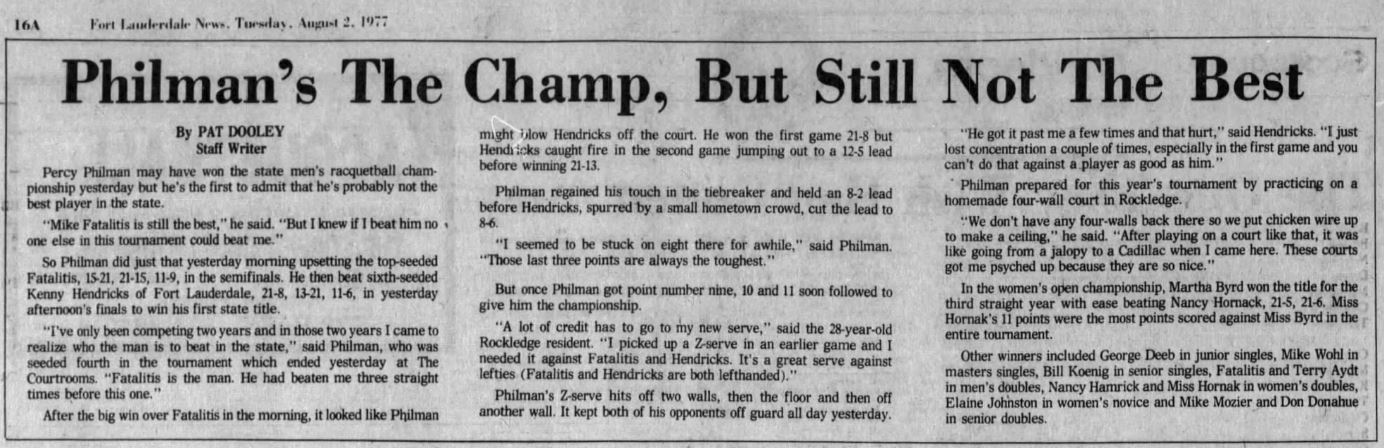

1977

July

August

1976

ESPN - 30 for 30 Shorts - When the King Held Court

Back to Top

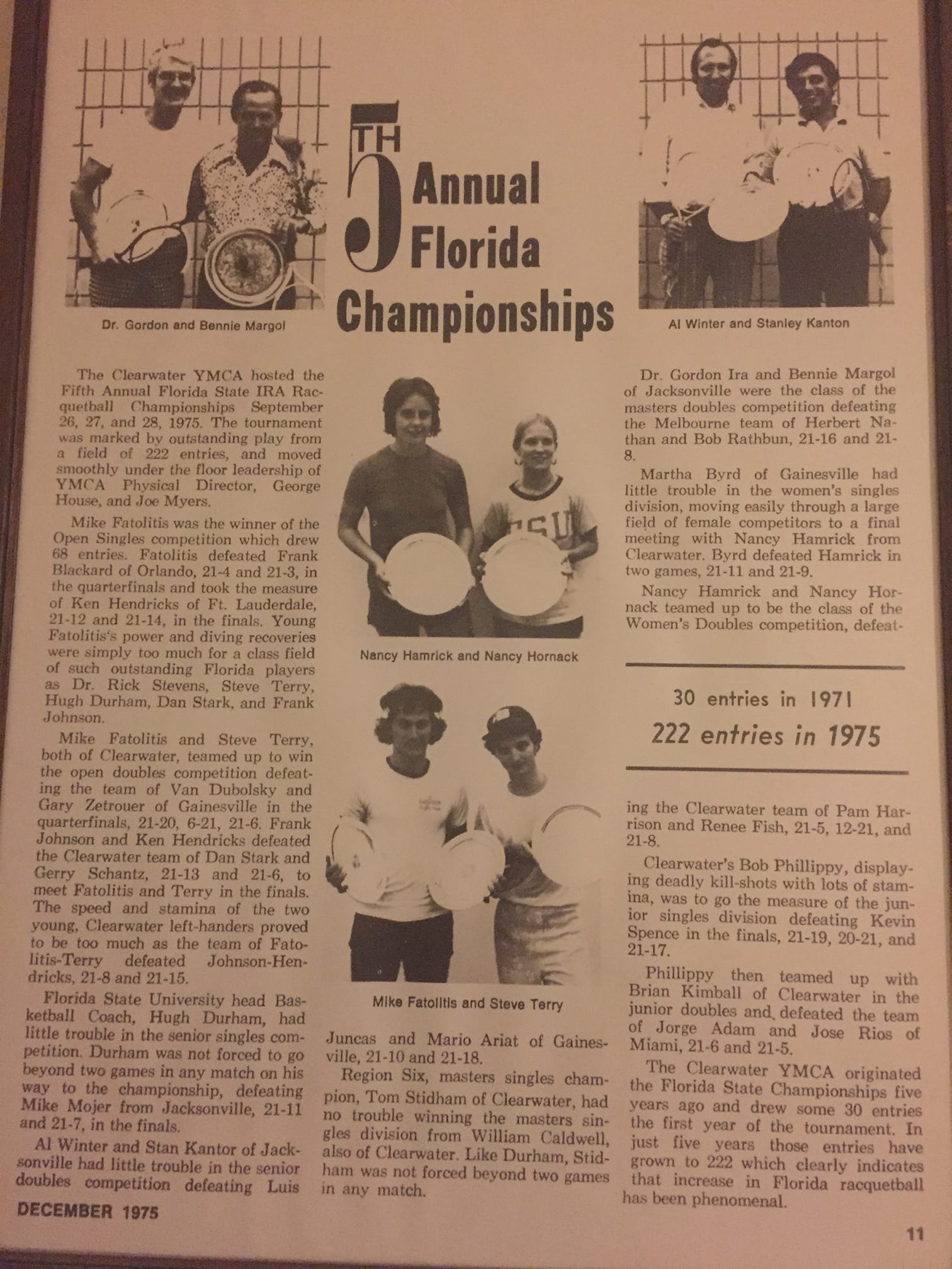

1975

1975 Florida State Singles Championships Newsletter (December 1975)

Graceland: Racquetball Building - Ashley Drew documentary on Elvis Presley's Racquetball Building Layout

1974

May

September

Vintage Beginning Racquetball Instruction with Steve Strandemo 1974

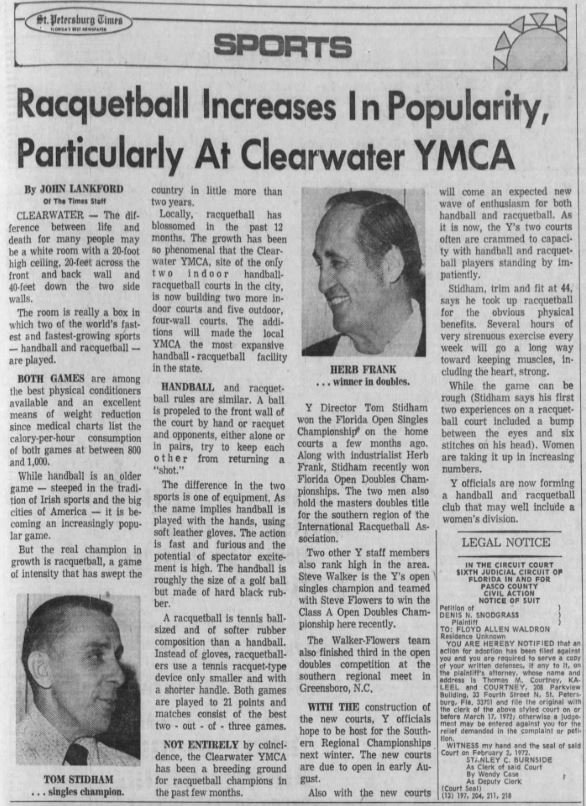

1973

March

October

Back to Top

1972

January

1972 Handball vs Racquetball Paul Haber (Handball - Chicago) vs Bud Muehleisen (Racquetball - San Diego)

February

September

October

Back to Top

1971

October

Back to Top

1970

1970s ad for AMF Volt Racquetball

Starring: Charlie Brumfield, Steve "Bo" Keeley, Steve Serot, and Steve Strandemo